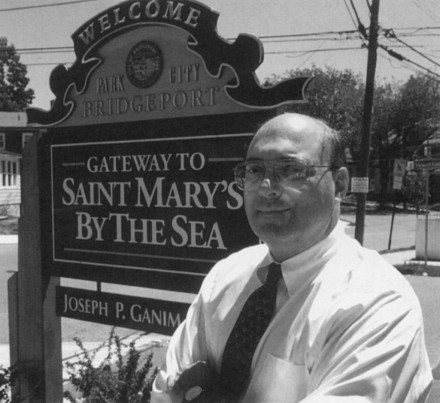

This is the second installment of Joe Ganim’s early years as mayor

Slowly, the city began to inch out of the abyss. The around-the-clock hours of reversing red ink made Ganim’s eyes bloodshot. Whatever funds his municipal tourniquet saved went back into beefing up the strength of the police department to fight crime.

Ganim reorganized city departments, hired highly credentialed department heads, found innovative ways to raise revenues without dipping into taxpayers pockets such as selling off delinquent tax liens to a private collection firm, negotiated fair union agreements, transitioned welfare recipients from dependency to self-sufficiency, convinced important city businesses to keep their tax dollars and jobs in the city. Ganim also managed to attend to quality-of-life issues such as the city’s popular library system, which had been plagued by dramatic cutbacks. Ganim found the money to increase library hours at all neighborhood branches.

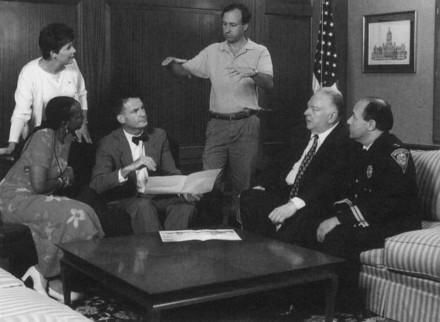

With the help of Police Chief Thomas Sweeney, Bridgeport’s first top cop hired through a national search, walking patrols and police precincts provided increased security. Ganim hired more than 100 police officers, which eventually led to the sharpest decline in crime in Bridgeport in 25 years. Championed by Ganim’s Public Facilities Director John Marsilio the city launched an unprecedented citywide street paving and beautification program, demolished hundreds of dilapidated buildings and transformed vacant lots into new parks.

Creative department heads such as Marsilio became one of the hallmarks of Ganim’s administration and won credibility with voters and the business community. Dennis Murphy, whom Ganim appointed chief administrative officer, Jerome Baron, finance director, Michael Freimuth, economic development director, Robert Kochiss, director of Policy and Management and Mark Anastasi, the city attorney, became the nucleus of a management team that won union concessions, balanced budgets and improved services.

Wall Street took notice. The Manhattan-based municipal bond rating agencies that freaked after the bankruptcy filing under Mary Moran rewarded the city’s recovery by upgrading Bridgeport bonds to investment grade.

Newspaper articles and headlines told the story; the city and its people were working their way back.

Hartford Courant: In Bridgeport, Rebound is real

Waterbury Republican: Bridgeport Rebounds

New Haven Register: Bridgeport regains its fiscal health

Connecticut Post: Ganim rescues Bridgeport from the brink of bankruptcy.

In 1993, voters rewarded Ganim with a walloping 80-percent-of-the-vote victory. In 1994, the ambitious young mayor eyed the governor’s office after his ally Lowell Weicker decided against reelection. Ganim won the immediate backing of a Connecticut Post editorial. Despite Ganim’s early track record, Connecticut’s suspicious Democratic Party insiders were not ready to embrace the young mayor. This was not new to Ganim who experienced the same skepticism during his early political life in Bridgeport. Ganim ended up as the running mate to state Comptroller William Curry, the party’s nominee for governor, who lost in a close election to Republican John Rowland. President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary made a fundraising stop at the Bridgeport Holiday Inn on behalf of the Curry/Ganim ticket in October of 1994.

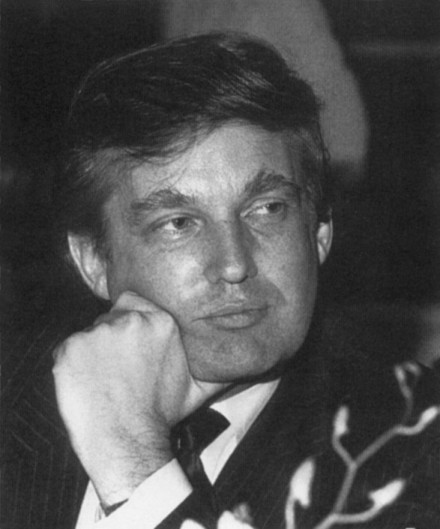

A major issue of the gubernatorial campaign was the expansion of casino gaming in Connecticut beyond the wildly successful Foxwoods casino in the rural town of Ledyard. Bridgeport’s untapped waterfront drew the attention of the highest of the high gaming operatives such as Steve Wynn, Donald Trump and the Mashantucket Pequots, operators of Foxwoods, all of whom proposed upwards of billion-dollar gaming establishments. Rowland supported gaming expansion in Bridgeport. Curry was against it. Ganim was in the odd position of agreeing with his running mate’s opponent. Bridgeport was in need of an economic shot in the arm. To Ganim, the gaming expansion was about bringing jobs, entertainment and tax dollars into the city.

In a non-binding referendum in March of 1995, city voters overwhelmingly approved a legislative vote on the issue. Both Wynn and the Mashantuckets spent millions lobbying the state legislature for approval while Trump did his part to torpedo the gaming bill, in a move to protect his Atlantic City interests from Connecticut cannibalism. Trump’s attitude was supremely capitalistic. “If expanded gaming is going to happen in Bridgeport, I want it,” he would say. “If I can’t have it, I want to kill it.” Trump unleashed his lobbyists to stop anyone else from getting in on the action, especially his archenemy Wynn. The two gaming moguls have spent many years devising tactics to blow up one another’s gaming proposals.

Robert Zeff, owner of the Bridgeport Jai Alai fronton, had a particular stake in the gaming legislation. He had secured state approval to transform jai alai into a greyhound track with the hope of installing hundreds of slot machines in his parimutuel facility. Zeff was Wynn’s local entrée, working to approve the gaming bill as furiously as Trump fought it.

Opponents to the gaming bill had significant legislative support, particularly from lower Fairfield County legislators, who cited traffic congestion, health issues and gambling addictions as reasons enough to derail the bill. In the end, the new governor could not convince his own Republican legislative base to support gaming in Bridgeport. Despite an impassioned plea on the senate floor from Bridgeport State Senator Alvin Penn, one of the spearheads of the gaming bill, the state senate voted down the bill. Bridgeporters experienced an ugly gaming hangover.

The setback was like a punch to Ganim’s gut and it became clearer waterfront revival would require a non-gaming action plan. An investment group led by former Bridgeport Hydraulic Company chief executive officer Jack McGregor, his wife Mary-Jane Foster and Physicians Health Services founder Mickey Herbert convinced city leaders that minor-league baseball would trigger community pride and an economic jolt like nothing in the city in decades. The location for a baseball stadium that intrigued Ganim and his Economic Development Director Michael Freimuth was the vacant Jenkins Valve building in the South End. Located right off Interstate 95, the five-acre parcel was owned by Donald Trump who purchased the industrial warhorse as a prospective site for a gaming facility. When the gaming bill failed to pass the State Senate, Trump lost interest in transforming the land. He also lost interest in paying roughly $300,000 in property taxes. “The assessment on this building is crazy,” Trump would say. “I’ve never seen anything like it.” Over the years, Ganim and Trump had developed a friendly relationship. One spring day in 1997, Trump fired off a letter to Ganim griping about the injustice of having to pay an extravagant tax bill for an industrial eyesore. Attaching copies of the tax bills to his letter, Trump explained that he wanted to explore a way to turn the building over to the city for a viable use.

Ganim wasn’t about to shed any tears for the Manhattan billionaire, but Trump’s lamenting triggered a Ganim idea. With Trump’s letter in hand the mayor dialed up The Donald and asked him to sign the deed to the property over to the city. Two polished negotiators were at work. Since he knew Trump wanted out of the building, Ganim felt the city was in a greater negotiating position. If Ganim had initiated the offer, The Donald most assuredly would have asked for a price tag well beyond the cost of the taxes. Ganim got his location for the ballpark and Trump walked away from the building.

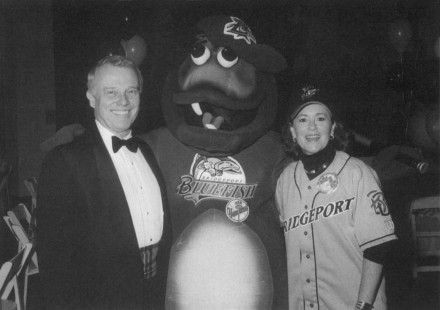

Backed by the support of Wall Street bond rating agencies and state assistance, Ganim led construction of a $19 million state-of-the art minor-league baseball stadium. City Councilmen Michael Marella, Bill Finch and Patrick Crossin rallied other City Council members to approve taxpayer dollars to build the stadium. Ganim’s prescription for the city was paying off and fish food was just what the doctor ordered. The city and the region got hooked on the Bluefish. In the initial years the ballpark came alive with full houses of 5500 per game. First-rate minor-league ball, family entertainment and attractions for kids in a safe environment. The city had an answer, finally, to the millennia-old question: where is there entertainment value in the inner city for kids and families?

The success of Harbor Yard inspired plans for a sports entertainment complex connecting the southern tip of Downtown to the South End. With funding from the state legislature, the city completed in 2001 a $40 million, 10,000-seat sports arena that has hosted big-name concerts, minor-league hockey, college basketball and the circus. Jack McGregor and Mary-Jane Foster, building on their Bluefish success, were the spearheads of the arena concept.

Let’s hope affordable housing across the street from the stadium is off the schedule!