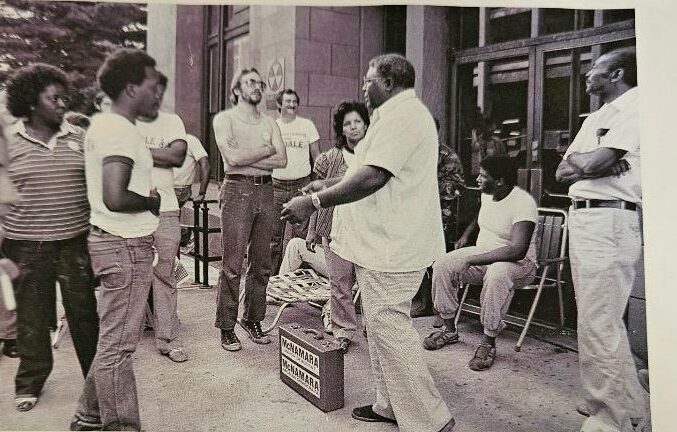

It’s the summer of 1983, the scene Registrar of Voters Office in McLevy Hall on State Street. A half dozen Democratic mayoral candidates and several other campaign hands are lined up at the door entrance jockeying petition sheets for the top line in the Democratic primary.

Two political warriors Charlie Tisdale and John McNamara, the city’s former chief legal counsel, are nose to nose. McNamara was one of the cutting needlers of his time against Tisdale, a former Harding High School quarterback who helmed the city’s anti-poverty agency and returned home two years prior after a stint in the Jimmy Carter White House.

Tisdale, whose campaign handlers had camped out the night before, backed down to no one.

In so many words Tisdale, the former quarterback, guaranteed McNamara either he goes in first or he’d shove a football up McNamara’s ass.

How did they get there?

In 1983 no one received the Democratic endorsement for mayor making it a wide open battle.

Convention night at the Three Door Inn was a study in chaotic name calling, bitter feuds and dubious electioneering. An endorsed candidate required 46 votes from the 90 member Democratic Town Committee. Young lawyer Tom Bucci backed by a sizable portion of party insiders banked the most with roughly 40 backers. The rest were largely split up between Tisdale, former Mayor John Mandanici and McNamara.

Round and round they went with roll calls and delegate negotiations during breaks amid hoots and hollers.

No one broke the logjam. On this night no kingmaker.

Tisdale supporter attorney Mark Gross, who sometimes had a peculiar communication style, took to the podium to nominate Tisdale for mayor.

To a jam-packed audience of pols and eager journalists awaiting the outcome, Gross took to the stage and declared “Who says you can’t support the moolinyan!”

It was more declaration than question. The place erupted in cheers and jeers.

Moolinyan is pejorative slang rooted in the southern Italian dialect word mulignane, (the g silent) meaning eggplant, its color a slur against Blacks.

Bridgeport’s political demographic was still largely White, a change that would arrive a generation later.

The night ended with no endorsement. All the candidates had to signature their way onto the ballot.

For Tisdale this set up perfect. He wanted this race wide open the Black candidate amid a large White field. Tisdale, a policy wonk, was a magnificent political organizer who inspired legions of young people to the table, Black, Brown and White. They were known as the Tizzies.

Tisdale would not campaign north of Capitol Avenue, a demarcation of sorts between the White and Black And Brown communities. He focused on his strength areas, particularly the East Side and East End. He knew the White vote would be split all over the place.

When the results filed in, as Tisdale had projected his vote overwhelmed the split electorate. He finished first by a comfortable margin, Bucci second, Mandanici third.

Tisdale became the first Black candidate nominated for mayor by a major party in Bridgeport’s history.

Now it was on to the general election.

In 1981, Republican Lenny Paoletta won the mayoralty in razor-close fashion over incumbent Democrat Mandanici.

After the 1983 primary Arthur DelMonte, who had secured a ballot spot on the Taxpayer Party line, ceded his ballot line to friend Mandanici.

Ralph Cennamo, another White candidate, also petitioned onto the general election ballot.

Some Democratic regulars, and White voters suspicious of Tisdale, split off with Mandanici. Electorally, the city was a much different place, White voters were the majority and the gap between registered Democrats and Republicans not nearly the 10 to 1 of the current registration.

Back then voting machines had party levers that provided coattails for other candidates. Pulling the party lever netted votes for all candidates on that line. Minor party and petitioning candidates had no lever, just a button to click.

Seemingly it was the best chance, considering the times, for Tisdale to win the general election, three White candidates splitting that constituency. It was a close, spirited, sometimes ugly, race.

Paoletta won the election with approximately 16,000 votes to Tisdale’s 15,000. Mandanici received 10,000 votes as a minor party candidate. Ralph Cennamo, as a petitioning candidate, picked up a couple thousand votes.

The citywide turnout eclipsed 70 percent. To compare, general elections for mayor in modern times are hard pressed to hit 25 percent.

Two political Lake Forest neighborhood mentors — the late Jack Goldring and Millie Steinhardt — tried to recruit me to get involved with the Tisdale Campaign. I declined due to the time constraints involved with work and pursuit of my higher education. Charlie was a Lake Forest neighbor who pioneered the desegregation of that neighborhood. He was very highly regarded by the LF neighbors in my family’s circle of friends, and with the endorsement of my previously mentioned mentors, it would have been a no-brainer to make the decision to get involved in his campaign had I had the time and energy to spare. I believe that Bridgeport would be a prosperous, highly regarded city if Charlie Tisdale had been elected mayor that year… Instead, we got…😈🤢🤮….

…and everyone on Charlie’s slate, myself included, won in the general election – everyone but Charlie! It still pisses me off.