Joe Ganim’s political resurrection has generated local, state and even national interest. Who is he? Where does he come from? What were his early years in office like? What follows is the first of two installments about young Joe Ganim, his growth as a politician and the initial years of his first mayoralty based largely from a year 2000 update of my book “Only In Bridgeport.” Yes, there are a few more chapters to add. Grab a cup of joe and read about Joe.

Pondering in his chair in Room 203 of Bridgeport City Hall, there were times when Joseph Peter Ganim thought he should have had his head examined. There he was, 32 years old, a successful young lawyer earning six figures a year, a house on the water in the city’s exclusive Black Rock neighborhood, soon to be married to the stunning Jennifer White with children on the horizon. He now was the youngest mayor in the history of Bridgeport fighting for his city’s life in federal bankruptcy court. His new salary was $52,000 a year. Lots of luck.

Under normal circumstances, the challenging task of governing the state’s largest city is consuming and overwhelming. The difficulties of running the city make most sane people flinch. The best mayors try to surround themselves with experienced advisers and hope for the best within the limitations of their power and authority. The city Ganim inherited in November of 1991 had hit bottom–financially, psychologically, emotionally. Huge tax increases and budget deficits were strangling residents and businesses. Soaring crime threatened the livelihood of neighborhoods. The bankruptcy filing that turned Bridgeport into a national symbol of urban decay loomed as the knockout blow that would force Connecticut’s largest city over the edge.

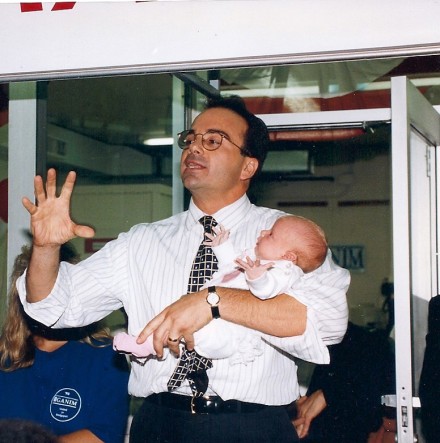

As a candidate for mayor, Ganim said all the right things: start with the basics to bring the city back. Fight crime, overhaul government, work with municipal unions to keep spending under control, improve schools, retain and attract business. A sound, basic campaign but nothing special. In November of 1991 he defeated Mary Moran handily to become the city’s 50th chief executive. Six days later he received the oath of office to govern the city his predecessor placed into bankruptcy court. Ganim soon learned running a campaign and running a city do not compare. Successful campaigns are run by MOM–money, organization and message. Successful cities are run on the force of will to carry out an economic road map, sharp instincts, sound judgment and relationship building. Few thought Ganim was up to the task. But Ganim emerged with something no other mayor in the modern history of the city brought to the office: a temperament uncannily even, very few highs, very few lows and knowing when to make a move. But above all, he was a patient, astute negotiator. This was his greatest strength.

Ganim learned how to negotiate early in life. “Living with four brothers and three sisters gave me a good start,” he said. He was born October 21, 1959 in Bridgeport Hospital. His father George Wanis Ganim Sr. was the son of Wanis Joseph Ganim, a Lebanese immigrant who settled in the United States around 1900 at age 18. He did factory work then established his own shoe-repair store on Barnum Avenue. Wanis married a fellow Lebanese, Rose Baghdadi in 1914, and they had eight children. Wanis had little formal education, but he read passionately, particularly history, philosophy and literature. He dreamed at least one of his sons would pursue a career in law, one of his own aspirations. The fruit and vegetable business he opened, which grew from a horse and wagon, to truck delivery business, to an outdoor site at North and Parrot Avenues, would pave the way. All of Wanis’ children were required to work in the family business. “My father didn’t pay us,” George recalled. “He paid our college tuition.”

George earned his law degree from Boston University in 1951. His brother Ray opened a law practice downtown in 1949, which George joined upon graduation. At 16 years of age, Josephine Tarick landed a part-time job for George’s fledgling law practice. Her father, Dimian Tarick, an oil and coal delivery man, was a Syrian immigrant and her mother, Anna DeBernardi, an Italian immigrant, arrived in Bridgeport from Naples around 1920. Josephine married her boss three years after George hired her. They didn’t waste any time raising a family. George and Josephine, like George’s parents, produced five sons and three daughters.

To people who knew young Joe, resiliency prevailed. He was only 5’7″ and 150 pounds, but that didn’t stop him from playing linebacker on the Notre Dame High School football team. The power of larger school kids forced Ganim to pick himself off the turf. He got up again and again. Quitting wasn’t a consideration. He studied political science at the University of Connecticut then graduated from the University of Bridgeport School of Law. He immediately joined his father’s law firm and succeeded in building a respectable general practice with a specialty in trial law. Delivering closing remarks to juries and settling domestic disputes paid the bills, but they didn’t offer the fledgling politician the kind of motivation to stick to a career in law.

He began making the rounds to introduce himself to Bridgeport’s Democratic Party leadership. At first, Democratic suspicion kept Ganim from making favor with party insiders. His father, after all, was a Republican. Nevertheless, Joe viewed his Democratic affiliation with opportunity. Republicans were eager to embrace him into their party. They needed new blood. If he could meld relationships within the Democratic Party and its stronger voter registration base with his Republican family stature this assuredly could make him a more attractive citywide candidate. But first he needed some seasoning as a campaigner. In 1988, at 28 years old, he challenged incumbent State Representative Lee Samowitz in a Democratic primary. Incumbency during this political period was not a safe haven for elected officials who drew the enmity of voters dissatisfied with the city’s bleak financial period and soaring crime rate. Samowitz, to his credit, successfully reminded voters of the money he brought back to Bridgeport from the state capital to aid their cause. He held on in a close race. Ganim’s respectable run, however, attracted consideration from party officials lining up with potential challengers to Democratic Mayor Thomas Bucci in 1989.

Bridgeport’s Democratic Party was a splintered mess, what veteran Bridgeport newspaper reporter James Callahan described as “a rat’s nest of infighting, backstabbing and double dealing.” As voters expressed frustration with the state of the city, politicians tripped over each other to find a candidate to run against Bucci. Problem was the anti-vote moving against Bucci was so splintered party regulars were unable to coalesce behind one candidate. Bucci faced opposition within his own party from five candidates, some party insiders, some party outsiders. Leading opponents against Bucci had small, but loyal built-in voter bases such as respected State Representatives Jackie Cocco and Robert Keeley and Bucci’s former economic development director Charles Tisdale who was the party nominee in 1983. Joe Ganim joined the fray, running an aggressive anti-incumbent and anti-tax campaign. He finished a surprising third in the six-candidate field.

The beating Bucci endured from his own party and voter frustration helped to ignite the campaign of Mary Moran who galvanized the anti-incumbent sentiment into her victory as Bridgeport’s first woman mayor. Ganim didn’t go away. In politics, sometimes you win by losing. His respectable losses to Samowitz and Bucci built prestige with party regulars and voters who wanted a mayor unhampered by the strings of party politicians. The message voters sent with Moran’s election resonated with Ganim. He would be respectful of the vote-getting ability of the party faithful, but would not sell his political soul to run the city. In exchange for support, it was traditional for Bridgeport Democratic candidates to cut their deals with party district leaders. District Leader A cuts a deal for parks director, District Leader B cuts a deal to become economic development director. Ganim wanted to be mayor, but not if party politicians were anchored to his governmental decision-making. In addition, he had an easy, disarming style that established experience beyond his years. Self-assured, he felt he could get elected without making promises. Besides, becoming mayor of Bridgeport had become either a nasty toothache or a political dead end. At $52,000 a year there were not a lot of takers for the job. The new kid on the block Joe Ganim had become the Democratic candidate for mayor.

The Ganim versus Moran showdown was classic blue-collar campaigning. In an attempt to highlight the 32-year-old Ganim’s youthful inexperience, Moran took to calling Ganim “Joey.” She also tried to convince voters that Ganim’s partial upbringing in the bucolic neighboring town of Easton disqualified him from being chief executive of Bridgeport. Ganim reminded voters time and again that Moran was disconnected from the myriad of city issues such as public safety and finances. A flashpoint he cited was Moran’s taxpayer purchase of a new Buick Park Avenue sedan during the height of the city’s fiscal crisis. When the votes were tallied on election night Ganim emerged with a comfortable 5000-vote plurality.

The day after his victory celebration the mayor-elect set up an impromptu meeting with Governor Lowell Weicker in the governor’s office. The contrast between the two men in both size and personality couldn’t have been more dramatic. Weicker was an indomitable, bombastic, brooding personality, towering in stature at 6’6″ who had served three terms in the United States Senate. Ganim, low-key, non-threatening and calm stood about one foot shorter with no public office experience. Just about one year earlier, Weicker jammed a contentious personal income tax through the Connecticut Legislature to repair the state’s sagging bottom line, after proclaiming as a candidate for governor that an income tax would be like “adding fuel to the fire.” Weicker drew an intense amount of public heat, but the income tax would prove a savior for state (and Bridgeport) finances. Weicker was particularly appalled by Moran’s bankruptcy filing. As a child of the state, Bridgeport’s fiscal bleeding had a direct impact on the state’s finances and bond rating. Weicker wanted something from Ganim, immediate withdrawal of the bankruptcy. Ganim wanted something from Weicker, dramatic state help to close an evil $18 million budget deficit, a projected $250 million budget deficit by the end of 1997 and a credit rating of junk bond status.

Weicker was joined at the meeting by his budget director William Cibes who also chaired the Bridgeport Financial Review Board. After a few obligatory congratulations, Weicker wasted no time.

“Okay, if you do your part, I’ll do mine,” Weicker said. Over the course of the next several months Weicker implemented a series of measures to help the ailing city. Concurrently, Ganim began the process of withdrawing the bankruptcy petition and won Weicker’s confidence.

With Weicker’s help, Ganim successfully retained major employers such as Chase Manhattan Bank of Connecticut and Southern Connecticut Gas Company; moved vigorously to clean up the disgraceful “Mount Trashmore,” a 30-foot-high, two-block pile of illegal demolition debris from the East End; found a new home for Housatonic Community Technical College at the site of the vacated Hi-Ho Mall; and secured the State Police master barracks for southern Connecticut, more than 100 troopers relocated from Westport to Downtown Bridgeport. Weicker also had the state purchase Beardsley Park and its zoological gardens from the city for $10 million, providing a much-needed infusion of cash. The state also assumed financial responsibility for several other city functions such as operations of the city train station.

While Weicker did his part, Ganim began the job of repairing Bridgeport’s finances, infrastructure and beleaguered image. He was sort of like a swan on the water moving along effortlessly, but underneath paddling like mad. Ganim’s office and desk had the appearance of war-room intelligence. His desk featured piled-high stacks of paperwork of the city’s most immediate issues. Bankruptcy. Business Flight. Crime. University of Bridgeport.

Working to hold the budget together, Ganim and his labor negotiator Dennis Murphy convinced municipal unions of the desperation of the city’s financial condition and achieved roughly $10 million in concessions. They promised job security in exchange for zero pay increases for upwards of 24 months and unpaid furloughs for two weeks. Leading by example, Ganim also returned two weeks of salary to the city. It was a good deal for both sides. Ganim received breathing room for his budget. The city workers kept their jobs.

(Up next: City’s 1990s fiscal comeback.)

I knew Joe Ganim in his early years, in fact I helped Ann Migliore and Kathy Biafore set up his office. Ganim called me into his office and asked me to take a seat on the Park Board. He told me he would have me named VP and Cruz Rosa President as he wanted to keep the Puerto Rican population happy. I said okay. A short time later Ganim came to the Park Board and asked us to consider selling Beardsley Park to the state. As we talked this out I realized my vote yea or nay was going to decide this issue. There was heavy persuasion put forth by the administration. I met with Ganim and said I would vote yes to the sale if he would guarantee me he would not lease out the golf course as had been rumored. Joe Ganim gave me his word he would not seek to lease the golf course. I voted for the sale of Beardsley park because it would save the city. The golf course was leased but that is another story that would surprise people.

Andy, you have mentioned this before and I have a question for you, now you might not want to answer and if you don’t I’ll understand, did you get any support from your district leader or from other Park Commissioners?

My district leader wanted a yes vote. The vote was tied 4 yes and 4 no and I broke the tie. My district leader was Ann Migliore.

Remember, Ganim had leverage with Weicker. The State guaranteed the $58 million bonding package and defaulting on the bonds would require the State of Connecticut pay.

The austerity measures in 1992 also included the city council cutting its stipend by 50%, from $500 to $250. Later during the Ganim years they increased their stipends to the point today they vote themselves $9,000 per year. The city finances must be in good shape. Only one other municipality provides a stipend to members of its legislative body. New Haven Board of Alderman receive $2,300 per year.