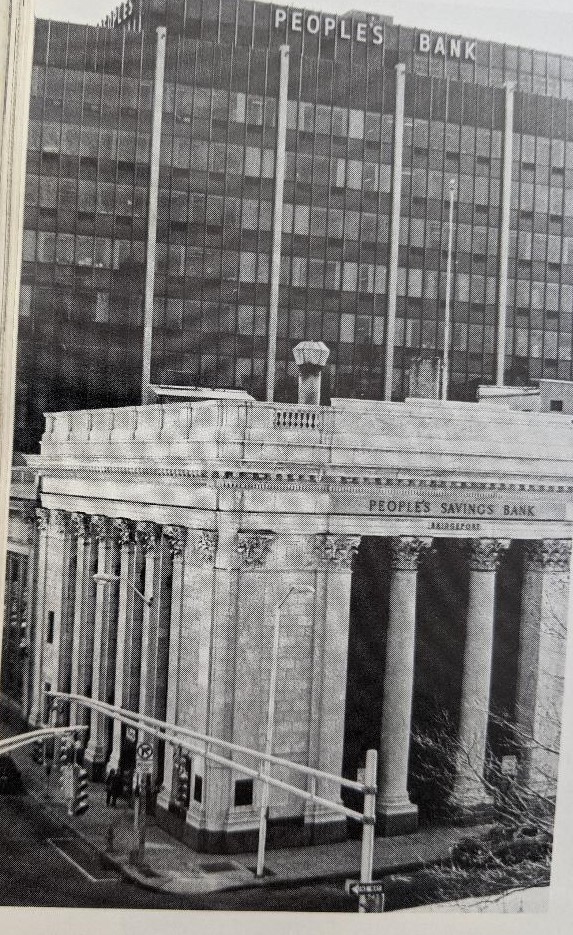

It began in 1842 as Bridgeport Savings Bank in the Downtown store of iron merchants George and Sherwood Sterling on Water Street. On Christmas Eve of that year the first account was opened by Fayerweather lighthouse keeper for his daughter Helen Moore. Four months passed before a single depositor withdrew any money, one dollar.

In 1843, for an annual rent of $12, the tiny savings bank moved to a second-floor room near Water and Wall Streets. In 1845, two weeks before Christmas, a fire spread from an oyster saloon and burned half of Downtown to the ground. Overnight the business center moved from Water Street to Main Street.

The emergence of People’s as a banking beacon for the city and state of Connecticut didn’t happen overnight. It took decades of jaw-boning organizational fortitude by its leaders including Sam Hawley, Nick Goodspeed, Jim Biggs and David Carson navigating thorny state banking regulations.

On Monday, the bank now known as People’s United, announced its purchase by M&T Bank for a cool $7.6 billion. Not bad measured against a modest start when $400 was the limit on the amount any one person could deposit at a time. The bank, according to officials, will serve as the New England regional headquarters for M&T Bank. A lot will be in play in the coming year including branch closures, consolidation of services and employment trepidation.

In 2008 I collaborated with Carson on his biography Bow Tie Banker which chronicles an immigrant’s unconventional rise as chief executive of the largest bank in America’s wealthiest state.

Here’s an excerpt from the People’s Bank chapter showcasing the institution’s social, financial, employment and stock growth.

•

In the spring of 1982, Sam Hawley, the 72-year-old scion of People’s Savings Bank, pulled into the parking lot at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield. He and Bob Huebner habitually met there to share the 50-minute drive to board meetings at Middlesex Mutual Assurance.

Hawley was the retired chief executive of People’s Savings Bank, turned chairman of the board, and Huebner, the chief operating officer of mighty Southern New England Telephone. These gentlemen were wired, whether it was access to bank lines…or phone lines. Both Hawley and Huebner served on the Middlesex Mutual Assurance board, and Hawley had asked Huebner to join the People’s board. During trips to Middletown, the two would discuss insurance and telephone industry issues. On this day, succession plans for the bank took center stage.

“What about Dave Carson?” Hawley queried. “How do you think he would work out as a banker?”

“Carson’s got a good mind. He can do just about anything with figures,” responded Huebner, chairman of People’s personnel committee.

“Okay,” said Hawley, “would you talk to him about it?”

Sam Hawley’s sentences could be as slight as the thinning hair on his head, but his words could move mountains. Just like that, he set in motion the luring of David Carson to New England’s largest savings bank. The bank’s trusted chief executive, Norwick R.G. Goodspeed, best known as Nick, was looking at retirement two or three years hence.

Having watched Carson in action for eight years, it was probable that Hawley had been thinking about Carson as Goodspeed’s successor long before he confided his thoughts to Huebner. Hawley was a legendary business executive in Connecticut, groomed for banking leadership from birth. Banking was his life. Still, Hawley was more than a man of deposits and withdrawals.

He was a community builder, a social progressive with a patrician thought process — the kind of leader who taught when he talked and learned when he listened. His chipmunk grin, horse-shoe dome head and reputation for thrift gave him a persona much like a reassuring uncle, forever offering encouragement. “Everything will be just fine.”

Samuel Waller Hawley was born in immigrant-rich Bridgeport, on Feb. 24, 1910. His family lived in Fairfield, however, and he was a WASP, through and through. His banking lineage traced back to his grandfather George B. Waller who assumed the presidency of People’s Savings Bank (then Bridgeport Savings Bank) in 1869.

Another grandfather, Alexander Hawley, served as executive officer and treasurer of the bank from 1882 to 1911. Continuing the tradition, Samuel M. Hawley (Samuel W. Hawley’s father), became president of the bank in 1921. Six years later, 17-year-old Sam tested the banking waters for the first time with a part-time position at Bridgeport Savings Bank on the eve of his freshman year at Yale.

Hawley graduated from Yale in 1931 with a bachelor’s degree in economics and earned his master’s from Harvard Business School in 1933. That year he joined the bank as a full-time clerk in the Mortgage Department. He was elected vice president in 1942, and a member of the board of trustees in 1948. For 19 years, from June of 1956 until 1975, when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 65, he served as chief executive officer. During this period, the bank’s assets grew from $198 million to $1.1 billion, with the branch network growing from three to sixteen, reaching from greater Bridgeport to Greenwich.

Hawley’s influence was cemented on small plots of land in the city and growing suburbs. Whether the property was in the North End of Bridgeport, or the burgeoning communities of Trumbull and Monroe, there was a pretty good chance that most any home bought or constructed during the 1950s was financed by the People’s mortgage department. Bridgeport’s middle class, enjoying the prosperity made possible by their industrial boomtown, and the wartime economy, wanted modern homes and expansive properties.

Hawley was ready for the housing explosion. People’s began to mass-market mortgages and attractive Veterans’ Administration loans. The bank also encouraged customers to save, instituting a variety of new savings services that made it easier for depositors to stow a few extra dollars a week.

Hawley’s banking leadership was complemented by a concern for social values. People’s reached out to the community in the areas of public housing, education, employment and the arts. During the searing days of the 1960s civil rights struggle, Sam Hawley pulled together white and African-American business leaders to discuss ways to assimilate races through job creation and opportunities. He also formed a Board of Counselors, comprised of neighborhood and political leaders, which became intimately involved in the bank’s role in the community.

During the summer of 1965, hot days scorching America’s cities got even hotter as civil rights unrest tested the nation. Hearing rumors of an impending riot in the city, Hawley placed a phone call to a young African-American lawyer, John Merchant. Hawley knew Merchant through involvement with Bridgeport’s anti-poverty agency, Action for Bridgeport Community Development, which had strong ties with inner-city neighborhoods. Hawley asked Merchant if he would investigate the rumors and call him back.

Merchant remembered the call clearly, with a tinge of disbelief. “I waited 15 minutes and called him back. I said it’s only a rumor.” While he had the bank chief on the phone, Merchant had a couple of things to add. “We really don’t make a habit of announcing our riots, and secondly, I don’t think it’s a good idea for you to call me about these issues unless you are going to talk to me the other ten months of the year.”

Hawley did not hesitate. “You’re right. What shall we do about it?”

For the first time, Bridgeport area leaders sat around a table with black community leaders. They discussed racial tensions, minority hiring, labor issues, and housing loans – developing bonds that worked for both sides. Merchant, a retired naval officer, coined the group the 1800 Club, named for the organization’s 6 p.m. meeting time. Merchant’s standing with the bank led to his appointment, the first black so named, to People’s board of directors in 1967.

If Hawley’s progressive attitudes and open-mindedness were celebrated, his fondness for frugality was legendary. He did not like to spend a penny more than required, whether it was the bank’s money or his own. There was the time in the mid-1960s when Hawley invited a new employee to lunch at a small eatery about a block from the bank’s branch on East Main Street. The young man ordered a tuna sandwich and his boss a cheese sandwich.

When the bill arrived, Hawley looked at his underling. “Why don’t you pay for this? Put it on an expense ticket. I don’t have any money with me.”

Neither did the young employee. Not a nickel. Mortified, the young man left Hawley at the luncheonette, hurried to the People’s branch and presented an expense ticket for a few dollars to cover lunch.

That was Sam. He wasn’t the kind of person who’d leap for the bill when it arrived. When it came to business, however, Hawley could examine the big picture without spending big money. More office space, to him, meant more bodies, which meant more costs. He did not want more space in the bank, unless it took the business to a new financial level.

People’s had thoroughly outgrown its space when he decided to build a new bank headquarters in 1965. The most appropriate location, however, was next door to the main office – which was occupied by a Greek diner. He found that the owner lived in Greece, and did not want to sell. Hawley, as he explained during an interview in 1992, decided to visit him in person, in Greece.

“Well, he was a pretty nice old guy. He said if the president of the bank came all this way to see me, I’ll take care of it. He lived in a little village of only about 300 people. He took me to his daughter’s house. It had no floor in it, just dirt and two lean sheds — that was their house. They lived in real poverty. Here, this fellow owned this piece of America. He owned land free and clear next to the biggest bank in town. Everybody wanted to own a piece of land. It’s a born instinct to hold onto a piece of land if you can get it, so he was not about to let it go. But he finally did and even came to the United States and gave us the deed. It worked out fine.”

The bank paid the man $35,000 cash for the deal. He put the money in a People’s savings account, where it stayed for years.

One thing about Hawley. He had no airs. What you saw was what you got. For the most part he asked questions and listened. He was also a master at understanding customer conveniences that led to more business.

Place bank branches next to food stores in shopping centers, he’d say. If people go to the food store, the branch is right there and you get the business. Don’t locate branches in out-of-the-way places where customers have to make a special trip. After World War II, People’s Savings Bank followed the returning GI to the suburbs, first financing the contractors that were building shopping centers and then placing branches there.

Hawley also had a genius for hiring the right talent at the right time. Goodspeed was one of them. A bright, hulking lawyer with a rapier wit, Goodspeed had a reputation for setting off fire alarms with his exuberant pipe smoking. In 1967 Hawley asked Goodspeed, an attorney at the Bridgeport law firm of Pullman, Comley, Bradley and Reeves, to join the bank – with the expectation of succeeding him. Goodspeed had been handling the bank’s legal matters.

Interviewed in 1992 about his switch in careers, Goodspeed reflected, “Psychiatrists say that every man should change jobs, or change wives, at least once in his life. I like my wife, so I decided I’d change jobs.”

Goodspeed also had a mission. Savings banks were generally sleepy little places for customers to deposit money and receive loans for residential houses. They were dwarfed by commercial banks, which, by Connecticut law, had more favorable legislative powers. In particular, state laws allowed checking accounts only at commercial banks.

In 1967, People’s was a savings bank with assets less than $500 million, and 250 employees and 10 branches. A passbook savings account was the bank’s only savings instrument and a 25- year, fixed-rate loan its one type of mortgage.

Governmental regulation stymied savings bank diversification. Commercial banks had all the advantages. Goodspeed’s goal was to achieve full banking powers for People’s and other savings banks. Change would not come easily. Not only did Goodspeed have to convince a majority of state legislators to change laws, he had to contend with commercial bank lobbyists, who gladly funded the political campaigns of legislators who kept the status quo.

“Commercial banks realized they had the best of both worlds,” Goodspeed explained in 1992. “They had checking accounts. They had savings accounts. They had everything. They didn’t need any more banking powers. The last thing in the world they wanted was to let savings banks in on their turf. They told the legislators to just leave everything the way it is. Savings banks are different. They don’t have stockholders. They don’t have to pay dividends to investors. They don’t pay taxes, the way we do. That was true, once upon a time, that savings banks actually didn’t have to pay the same kind of corporate income tax, federal corporate income tax, that commercials did, so they had this argument that savings bank aren’t entitled, don’t deserve, don’t need checking accounts. It was hard to compete.”

Norwick R. G. Goodspeed was born in Newton, Massachusetts. He moved to Fairfield, Connecticut in 1931 when his father took a position as a stockbroker in New York City. Goodspeed graduated from Yale University and Yale Law School before joining Pullman, Comley, Bradley & Reeves, the bank’s legal representative, in 1945. He became the firm’s leading expert on zoning, enjoying close relationships with major developers and politicians throughout Connecticut, and particularly, Fairfield County.

When he joined the bank in July of 1967, within a matter of months Goodspeed was appointed to the legislative committee of the National Association of Mutual Savings Banks. NAMSB had supported a bill in the Connecticut General Assembly to allow savings banks to offer checking accounts. At that time, Connecticut had about 70 savings banks, and roughly the same number of commercial banks, with total assets exceeding commercial banks. But savings banks had little influence, recognition or voice in Hartford. Commercial banks, including Connecticut Bank & Trust, Connecticut National, Hartford National and Citytrust provided banking services to the state and its municipalities, managing almost all payroll accounts, pension funds and bond issues.

Savings banks were created to provide a financial service on a non-profit basis to community people – because nobody else was doing it. The typical savings bank was non-profit, or at least non-stock. All mutual institutions operated like a hospital or university, directed by a board of trustees with fiduciary responsibility to manage the institution for the benefit of its depositors and borrowers. Savings banks were a place for people to save, offering modest returns. Those monies were invested in single-family mortgage loans or government bonds.

For decades, People’s Savings Bank had a deposit rate ceiling fixed by the federal government. The bank couldn’t pay more than five percent interest. In general, the bank paid four percent to depositors for use of their money, and the money was lent out for home mortgages at seven percent. That small percentage difference paid salaries, utilities and taxes. As long as times were good, there was no need to change the laws.

Commercial banks were happy to offer checking accounts and make commercial and automobile loans. They had checking account money, including large corporate accounts and, by law, could not pay interest on them.

Goodspeed had some experience in politics, having served on the Republican Town Committee in Fairfield. He knew enough people in the legislature to immediately start visiting old friends and ask for their thoughts and support.

Commercial banks were beginning to compete for savings deposits. Federal regulation had imposed interest rate caps and commercial banks were restricted to offering one percentage point less than savings banks. The number got narrower to the point where savings banks could pay one half a percent more than commercial banks. This was later whittled to one quarter of a percent.

One of Goodspeed’s friends, an attorney serving in the state legislature, told him the facts of life: “Nick, I understand what you’re telling me, but I have to be honest. I get legal business and political contributions from my local commercial bank. I’ve never received a penny’s worth of either political contribution or business from the savings banks in town.”

That lawyer ended up as a state judge, nominated by a governor who also benefited from commercial banks’ campaign contributions. Goodspeed realized that his buddy didn’t see any great moral problem in maintaining the status quo. It was a fact of life that contact, communication and playing the political game produced a favorable climate for commercial banks.

So Goodspeed dared to go where no savings banker went before. For many corporate leaders, it was viewed as almost dishonest to lobby political stick-up artists for laws that would help their businesses.

Goodspeed looked at it differently as a forum to revolutionize banking in Connecticut. The commercial banks played, so he would, too. His goal: an even playing field. Goodspeed reached out to political and legislative leaders in small, but persuasive doses, explaining the virtues of a progressive banking system: how it would build the economy, add jobs and grow the tax base. The phone calls were ceaseless, testimony at state legislative hearings aplenty and the governmental reception was typically slow. Each year, Goodspeed’s lobbying efforts opened up a few more eyes, tugged at the interests of legislative leaders and built a base of support in Hartford.

His persistence gained momentum in the early 1970s. He talked to his associates in savings banks and they formed regional committees to persuade every bank to build a relationship with its local legislators. It didn’t matter which side of the political aisle they were on. The word was to show up, get involved, make your pitch and — by the way — write a check to the legislator’s campaign fund. Savings bankers began attending the Jefferson-Jackson Day dinner for Democrats and buying a table at the Republicans’ Lincoln Day dinner. Campaign contributions to individual legislators commenced.

And guess what? Many legislators were also attorneys. Commercial banks were smart enough to realize that if you wanted assistance, it helps to send legal work to lawyers who can help with your legislative issues. Soon savings banks also sent legal and mortgage work to lawyers who were members of the legislature. In fact, Goodspeed saw to it that not all People’s legal work went to his old firm, the bank’s entrenched legal adviser. People’s had mortgages all over the state. It didn’t make sense for Pullman & Comley to do the work upstate, when an attorney with legislative contacts could handle it.

In 1971 savings bankers won a breakthrough, a 17-person commission of legislators and bankers ordered a study of the whole issue.

“If a bomb ever dropped on the Capitol,” Goodspeed remembered one person saying, “it would wipe out the whole banking system of the state.”

After two years of witnesses, and hearings, Connecticut legislators concluded that savings banks really had a point. It didn’t make sense to allow one-stop banking at commercial banks, while limiting financial services at savings banks.

In 1974, Republican Governor Thomas Meskill signed a bill authorizing personal checking accounts at savings banks, effective in January 1976. “So even when we won the legislation,” Goodspeed pointed out, “part of the price the commercial bankers carved out, was that we didn’t get authorization right away. We had to wait a year and a half.”

In 1975, Hawley reached his mandatory retirement age of 65 and Goodspeed became the CEO of People’s Savings Bank. The next major breakthrough for the bank was branch expansion into areas such as New Haven and Hartford. Those were days, Goodspeed recalled, when the state bank commissioner had to be convinced a community could use another bank.

“If another savings bank already had an office in town, you had to go to the bank commissioner, go through a formal hearing process and argue with all kinds of statistics based on population, average deposit size and how many people per banking office and so forth.”

Goodspeed convinced several smaller independent banks in New Haven and Hartford that their institution, their employees, and ultimately their customers, would fare better if they were part of a larger institution.

The bank was growing under Goodspeed’s legislative leadership. With the authority to offer checking accounts, the next step was to transform the bank into a full-service financial organization. A new executive vice president was hired, economist Lloyd Pierce, who as director of education of the National Association of Mutual Savings Banks, had set up a college for the nation’s bankers. The school, which offered courses on everything from mortgage lending, to classes for bank presidents, was located on the grounds of nearby Fairfield University.

In those years, People’s also purchased a fledgling telephone bill payment service and system from Seattle First Bank in Washington state. Officials there were disappointed in the experimental results. Pierce believed that further development and marketing of the pay-by-phone system could elevate the bank’s stature with more financial services.

Pierce placed a young vice president, Jim Biggs, in charge of new product development. Recruited by his neighbor, Sam Hawley, right after graduating from Dartmouth College, Biggs came from one of the established families in Fairfield. Looking at new products, Biggs hired a research organization to conduct focus groups. From this information, a survey was created and presented to roughly 1,000 consumers in the greater Bridgeport area.

In 1974, the survey became the stimulus for Pay-By-Phone, a small call-in service staffed by three employees in the basement of the bank building. Customers could pick up the phone, call the bank and explain what bills they wanted paid. Initially the service was solely for customer convenience, but it brought the bank a lot of public attention and a growing customer base.

The bank soon formed a small department called Consumer Financial Services, creating a service package that combined checking, bill-paying through Pay-By-Phone, a statement savings account and a personal line of credit. All were included in one monthly statement. For the first time in the country, these services were being combined, and a bank consultant predicted that 4,000 accounts would be opened in the first year. In fact, 25,000 new accounts were opened.

Three years later, in 1977, automated teller machines became popular. All of the bank’s major competitors were marketing “banking-at-sunset” service to customers. But consumers were slow to use this dramatically new concept. People’s did not buy the machines because the bank’s checking account base was too small to justify the cost.

Len Mainiero, a bank executive vice president, presented an idea during a planning session: Why not share another bank’s ATMs? Biggs approached John Topham, president of Citytrust Bank, and asked if Citytrust would consider letting People’s customers access their accounts at Citytrust ATMs — in exchange for a fee paid by People’s.

Topham liked the idea of additional revenue for his bank from machines that were already in place. For People’s, the plan offered another service to match its competition without a large capital outlay. The agreement was the first shared ATM arrangement in the United States.

Goodspeed wasn’t finished trying to level the banking playing field. In 1982, it was still illegal for a savings bank to hold a commercial bank charter. Soon, Goodspeed purchased the assets and liabilities of a commercial bank in Stamford – but not the charter. Connecticut’s commercial banking world immediately took it to court. In the end, People’s won the case in the U.S. Supreme Court. When Goodspeed heard the news, he was so excited that his pipe smoke set off the bank’s fire alarm.

People’s was now New England’s largest savings bank and among the top 10 in the nation. With more than $2 billion in assets, approximately 40 offices in Connecticut, and more than 1,000 employees, People’s was growing beyond imagination.

Lennie, I remember you posting part of this story in the past, especially the portion about John Merchant and what I find so sadly true even to this day in 2021 that the same mindset exist in Bridgeport goverment at every level. Thanks Lennie for sharing this again.

During the summer of 1965, hot days scorching America’s cities got even hotter as civil rights unrest tested the nation. Hearing rumors of an impending riot in the city, Hawley placed a phone call to a young African-American lawyer, John Merchant. Hawley knew Merchant through involvement with Bridgeport’s anti-poverty agency, Action for Bridgeport Community Development, which had strong ties with inner-city neighborhoods. Hawley asked Merchant if he would investigate the rumors and call him back.

Merchant remembered the call clearly, with a tinge of disbelief. “I waited 15 minutes and called him back. I said it’s only a rumor.” While he had the bank chief on the phone, Merchant had a couple of things to add. “We really don’t make a habit of announcing our riots, and secondly, I don’t think it’s a good idea for you to call me about these issues unless you are going to talk to me the other ten months of the year.”

Hawley did not hesitate. “You’re right. What shall we do about it?”

For the first time, Bridgeport area leaders sat around a table with black community leaders. They discussed racial tensions, minority hiring, labor issues, and housing loans – developing bonds that worked for both sides. Merchant, a retired naval officer, coined the group the 1800 Club, named for the organization’s 6 p.m. meeting time. Merchant’s standing with the bank led to his appointment, the first black so named, to People’s board of directors in 1967.

Now look at the history that was going on in America during that time frame with same issue about race.

During his inaugural parade, President John F. Kennedy noticed that there were no African Americans in the Coast Guard Academy cadet unit marching in the parade. He told his speechwriter, Richard Goodwin, “That’s not acceptable. Something out to be done about it.” Goodwin called Secretary of the Treasury C. Douglas Dillon the next day and Dillon ordered the Academy “to scrutinize the Academy’s recruitment policy to make sure it id not discriminate against blacks.”

I remember when I was a bagman for the Fairfield DTC Attorney Noel Newman was chairman, I was in charge of a fund raising book, Newman told me to go pick up a check in Greenfield Hill from John Merchant. Much to my surprise he was a black man living in Greenfield Hill, he gave me a check for $250. I was flabbergasted he put my book over the top that year, Newman said he always contributes to DTC.

I remember a couple of years ago I needed to figure out what happened with some IRA’s I had with People’s. I stopped by a branch in Branford and asked them if they could look into the matter. This woman said to me, “sure no problem.” We will need to charge you so much to do the research. If we find something the helps we will need to charge you so much per page. If we need to do additional research it will be blah, blah, blah. And if you want certified copies they’ll be blah, blah, blah.

I stood up and looked at her and said with a raised voice “no thanks. I have had a continuous account with you people for probably 50 some odd years. And this is the thanks I get in return. We can do it but you have to pay. No thanks. I’ll figure out another way to do it.” And I did.

When recently People’s announced some closings some one from another branch called just to say hello, that they appreciated my business and if I had any questions, please call. Most of my business with that branch had to do with currency exchanges for my travels overseas.

Don’t know if it had to do with how one branch values customers over another or how they view themselves and their position in the banking industry at any point in time but I know this. I have no loyalty to Peoples now and will probably be ending or seriously changing my relationship now.

I will wait until Lennie has enough time for another cup of joe, wipes the sleep out of his eyes and does whatever else he does in the morning (maybe take the dog out for a walk) before I really start blogging about the headline that caught my eye.

“Cops ask for delay of deadly force rules until 2022.” 18 month delay?

How many more deaths will we experience while police get trained on deadly force law? Or is it really an open season before we get serious.

Not only does Bridgeport deserve change now but Rep Steve Stafstrom, co-chair of the Judiciary Committee, serves as a representative of the city.

Bob, I am also concern about “Cops ask for 18-month delay and loosening of deadly force rules.” I’m back to my old question that I never saw an answer, what was in former Police Chief Charles Ramsey’s $25,000 report of his look into the Bridgeport Police Department?

Ron

And I am asking why do we have a City Council President who does NOTHING???

I am beginning to believe she should resign today. I believe she said that Chief Ramsey is an elderly gentlemen and his wife was worried about COVID-19. And she found that acceptable.

She has had an ad hoc committee looking into the policing in the city for at least 9 months and we have seen NOTHING.

But if she gets mad at other council members for whatever petty, personal infighting she acts.

Take a no confidence vote of the City Council and let’s see where they stand.

Ron

Did you see that bit on the news where 2 Orange County police officers started hassling someone for jaywalking even though experts say he really wasn’t jaywalking. They threw him to the ground, one of the cops said ‘he’s got my gun’. The other one shot and killed him.

They then showed a still photo of the guy grabbing for the gun to justify it.

Fortunately they pieced together the full story my using the verbiage from the cameras on the uniform, other street videos and other cameras.

Now what training needs to be done for a cop to know this ain’t right? Or maybe it’s training then to cover it up better.