Twenty-five years ago, the city celebrated the grand opening of Bridgeport Center, the new corporate headquarters for People’s Bank, today called People’s United Bank. The tallest building in the city, it was an $80 million construction project led by then-Chief Executive Officer David Ellis Adams Carson who turned 80 years old on August 2. When you talk about business impact and philanthropic influence in Bridgeport, Carson’s legacy is to be admired with the likes of P.T. Barnum, industrialist Frank D’Addario and Betty Pfriem, former publisher of the Connecticut Post. I am fortunate to be Carson’s biographer. In honor of Carson’s birthday and the building that changed the city’s Downtown skyline, what follows is a chapter about the construction of Bridgeport Center from my book Bow Tie Banker. Grab a pot of Joe for weekend reading.

Shortly after 6 a.m. on April 20, 1986, Bridgeport Mayor Thomas Bucci and David Carson huddled on McLevy Green at the intersection of Main and State Streets in downtown Bridgeport. Camera crews, photographers and reporters were scattered nearby. Streets were closed. Interstate 95 was temporarily shut down and buildings within slingshot were covered in plastic, cloth and boards.

Downtown Bridgeport was about to experience something new in the city’s 150-year history: an imploding office building. The tired, but well-known Connecticut National Bank structure would make way for Bridgeport Center, new corporate headquarters for People’s Bank.

Bank, city officials and special guests gathered about 5:30 a.m. to watch from the People’s Bank board room at 855 Main Street, across the street. Enthusiasm was high as people waited for the implosion. But two guests watched quietly, with mixed emotions: Bronson Hawley and his mother, Barbara. The Hawley family name goes back to People’s founding in 1842, when Alexander Hawley, the bank’s first treasurer, was its de facto president.

Bronson was the nephew of Samuel Hawley, former CEO of People’s Bank, and the son of Alexander Hawley, who, for more than a dozen years, served as president and CEO at Connecticut National.

A People’s employee, Bronson had grown up in banking. His father had died two years earlier, in 1984, and his mother, who had great respect for both institutions, found the implosion difficult to watch. It was a poignant moment for them. Others, less personally involved, found it exciting, and crowded the windows. The countdown inside matched the one outside. Mayor Bucci, not Carson, was going to push the plunger.

Carson, a Republican, had built a friendly relationship with Bucci, the Democratic city leader, in the six months since his oath of office. Bucci’s predecessor, Republican Len Paoletta, had asked Carson to chair Bridgeport’s sesquicentennial celebration in 1986, lending his growing profile and enthusiasm to the cause. In the process, Carson had worked with many of the city’s Democratic leaders.

Knowing it would enhance the mayor’s public position, Carson asked Bucci to push the firing plunger. Plus, Carson wanted to avoid the possibility of a news headline blaring something like, “Banker Blows Up Competition.”

Bucci was more than happy to signal Bridgeport’s largest economic development project in decades. Within seconds, rapid-fire explosions, the kind heard at a fireworks conclusion, assaulted eardrums. Trigger points split the building joints and it fell like a flattened soufflé. A mass of dust, dirt and particles covered the downtown with a dense fog, wiping out visibility for four or five minutes. The sun had come up, but it was night again. Bucci jumped into the safety of his city vehicle; others sprinted hundreds of feet until they could see daylight. When the fog cleared, the building was gone, demolished into a large pile of rubble.

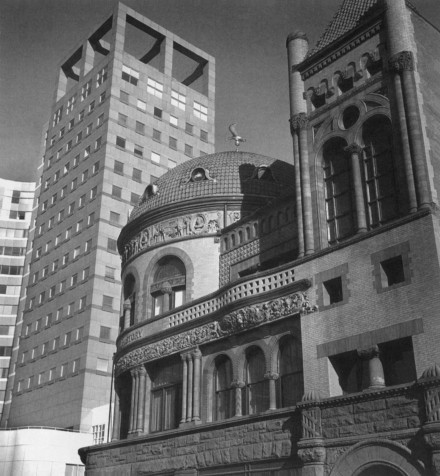

In a few years, Bridgeport Center–the new building–would be a recognized regional landmark, a 16-story statement by the bank’s chief executive, and a showpiece for the rebirth of a gritty city.

Building plans had been in the works years before Carson joined People’s. In 1979, Carson’s predecessor, Nick Goodspeed had negotiated with Bridgeport Mayor John Mandanici to acquire the site south of the old Connecticut National Bank building. By the time Carson joined the bank, People’s had nearly 2,000 employees. Bank mergers, a discount brokerage business and commercial banking had grown the bank beyond the existing building at 855 Main Street. People’s Securities Inc. and the bank’s commercial lending operations were already sited elsewhere.

Goodspeed and Sam Hawley had not settled on the scale needed to accommodate the bank’s growth. A confusion of initial drawings, possibilities and plans existed. Under these circumstances, Goodspeed and Hawley agreed on the logical thing: pass the project to Carson, who would be CEO when the building was underway. Carson didn’t envision a basic structure. He wanted something worldly to give visual testimony to Bridgeport’s economic rebirth and highlight his vision of the technological future of banking.

The first decisions necessary were to choose an architect, a construction manager and designate a project manager.

Carson preferred to hire an architect with offices within an hour’s drive of the site, essentially limiting his pool of candidates to Connecticut and metropolitan New York. A number of noted architects were interviewed, including Kevin Roache, Philip Johnson, Skidmore Owens and Richard Meier, with whom Carson had worked on the Hartford Seminary project. Carson wanted an architect sensitive to the needs and beauty of the interior, as well as the more commanding focus of the exterior.

In the end, he tapped Meier, who was a natural at this functionality because he had designed many impressive residential structures, where interiors were critical. Few architects design both the exterior and the interior of commercial buildings. Meier would do both.

Carson and Meier were simpatico, so much so that they started on a handshake. A contract was worked out months later, when plans were already underway.

For construction managers, the bank hired Gerald D. Hines Interests, a firm that had worked with numerous architects to build the Houston, Texas, skyline. Turner Construction, of New York, was chosen as general contractor.

First off, site issues had to be settled. The Connecticut National Bank building, at the corner Main and State, was on the state’s historic preservation list. Carson talked with CNB officials about air rights to construct the People’s building around the existing structure. CNB officials proposed an alternative: outright purchase of the building, with the proviso that a CNB branch and regional offices remain at their well-known “corner of Main and State Streets.” So that’s how People’s bought the building–and why a banking competitor’s branch would be located on People’s home turf.

At 248 feet, Bridgeport Center would be the tallest building in the city. Meier and Carson viewed it as a city within a city. Located one block from the Connecticut Turnpike, a Metro-North Railroad station and the Bridgeport-Port Jefferson (L.I.) Ferry, to some extent it became a transportation center with its 5-level atrium and central plaza out front. It would also be a structural counterpoint to the rundown factories edging the city’s transportation arteries.

The Bridgeport Center project also included a multi-million-dollar renovation of the city’s Barnum Museum. The museum, the only other structure on the Bridgeport Center city block, is a tribute to the 19th century showman and Bridgeport mayor P.T. Barnum.

In discussions between Meier, historic preservationists and bank officials, it was decided that the exterior of Bridgeport Center should complement the terra cotta stone of the Barnum. As a result, Meier incorporated 170,000 square feet of reddish-colored granite from Brazil into the People’s plaza and atrium floors. Bridgeport Center’s massive columns and walls were built of white enameled steel panels from Canada, creating a pleasing contrast to the reddish atrium floor and the gray accents in the entire structure.

Carson and Meier easily agreed on the essence of the building, how it would fit into its environment, serve the city and most importantly, function for the bank and its employees.

This would be a headquarters building with many departments and processes. A telephone banking call center has different design needs from the graphics and conference rooms required in marketing, or the luxurious open space needed for trust and financial services clients. During the coming weeks, Meier and his staff spent intensive hours interviewing People’s Bank executives to understand the working needs of the building.

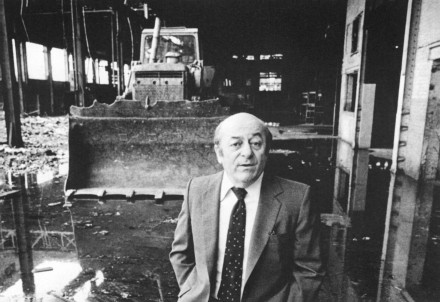

Carson also needed a bank officer to have daily contact with the principal firms, oversee construction, coordinate with others on the employee move-in and balance delicate egos. He chose Joe McGee, a young People’s vice president, who had cut his teeth in Washington politics working as an aide to U.S. Rep. Stewart McKinney. McGee reported directly to Carson. McGee had been hired by Hawley in 1980, about three years before Carson arrived, to oversee the bank’s urban renewal projects. As Bridgeport Center began to take shape, Carson asked McGee to shepherd land use approvals, keep construction on schedule and work closely with Richard Meier and his staff.

Carson’s primary rationale for tapping McGee was his experience on large-scale government development projects in Washington, D.C. And McGee, like Carson, envisioned Bridgeport Center as a first step in the city’s economic rebirth. McGee realized it wouldn’t be easy.

“David handed me a hand grenade,” McGee recalled. “Bridgeport Center under construction was a huge can of worms requiring decision-making on the spot. It’s not the kind of thing you do by committee.”

McGee’s early workload included applying for 115 governmental approvals and working with Bridgeport officials to retool the city’s antiquated infrastructure. Bridgeport was an old factory town and the new building required underground utility and power sources.

In an interview with The Bridgeport Light in 1989, McGee talked about his frustration with government bureaucracy. “There are so many levels of approval. It’s hard to know who is in charge. Dealing with this city is like trying to get a date with a girl with an unlisted phone number.”

McGee pushed forward. Imploding a building and cleaning up the site were monumental tasks. Before the demolition and cleanup came a frenzied competition for the removal work. The demolition industry had tentacles deep within the city’s political structure. Choosing a company to remove the debris–and just where it would end up–created serious concerns for a community bank. Government and environmental activists would keep a close eye on demolition in a city known for its illegal dumping grounds.

A local godfather actually sorted out the issues. Fiore Francis “Hi-Ho” D’Addario, who took his nickname from the nursery rhyme Farmer In The Dell, was among Connecticut’s high-profile industrial leaders. His interests ranged from slot machines in Atlantic City to asphalt in Bridgeport, and he stepped into the breach several months before the implosion.

Carson had met Hi-Ho when he served as chairman of the city’s 150th anniversary committee. Carson later described it: “I called the first meeting at eight one morning. At about 8:15 a.m., Hi-Ho, who I had not met before, roared into the meeting yelling ‘Who in God’s name called a meeting this early in the morning? I’ve never, ever, come to anything this early!'”

Later, they became good friends. Hi-Ho treated him to a helicopter tour of Bridgeport and Hi-Ho provided lots of support to the bank’s 150th year celebration.

Hi-Ho was right out of central casting–a short, squat, craggy-faced fury of street smarts and cunning negotiation. His Italian immigrant parents, Nicola and Louisa gave birth to twin sons in 1922, one dying shortly after birth. The other, Fiore, born with clubfeet, was the only surviving son of six boys, five of whom died at childbirth.

Two foot operations at age two left Fiore in braces for ten more years. What Fiore lacked in stature, he made up in guile. Hi-Ho would one day build an industrial empire and be the first person granted a casino license in Atlantic City. The feds had examined every aspect of Hi-Ho’s body, businesses and brethren and had come up with nothing illegal.

Bank officials understood the demolition world was not a club for Boy Scouts. But it would be better if the site were cleaned without grand jury subpoenas. Hi-Ho visited with McGee and Carson and said, in so many words, you don’t want to give the demolition to the low bidder. He would do the job at a reasonable price and smooth things out locally so the bank would not be embarrassed. Hi-Ho promised to pacify the debris haulers who wanted the job by hiring them to cart the remains to his landfill in nearby Milford.

Then on March 5, 1986, about six weeks before the scheduled implosion, D’Addario was aboard his private plane, cruising over a Chicago suburb, when the pilot lost control. The plane went down, taking the 64-year-old with it.

The state lost a business legend. David D’Addario, just 24 years old, lost his father. Young D’Addario had been groomed by his father to replace him, just not so soon. He was just two years of out Yale and now overnight was head of a powerhouse umbrella organization with dozens of business holdings worth hundreds of millions. He assumed the role of operating the mammoth business in the shadow of his legendary father.

Young David D’Addario was at the implosion, wearing work boots and hardhat. He recalled a conversation that day with Carson, who asked, “Can you do this without damaging anything?”

D’Addario’s crews had placed steel plates on area streets with sand on top to absorb the potential shock. Doug Loizeaux, who handled the implosion on behalf of a Maryland-based company, Controlled Demolition, explained the rationale. “One reason why they chose the implosion method was so the building could bow out gracefully, in a matter of seconds, rather than be hacked to death with a crane for months.”

Implosions are newsworthy and tricky. It turns out the bank building crumbled almost perfectly within its footprint. In the aftermath, D’Addario searched for evidence of damage. When all was done, the only breakage was a paperweight-size piece of limestone from the façade of People’s Cass Gilbert building across the street. McGee had the piece reset into the building, where it can be seen today, a little-recognized memento.

For D’Addario, whose father had died just weeks before, the implosion was a huge psychological passage. “The implosion was a real personal achievement for D’Addario as a company, and me, personally, because it sent a message that despite the loss of my father, the company was stepping into a whole new arena and succeeding.”

With the implosion a success, McGee focused on the building, trying to keep the process on time and on budget. He achieved the first goal. The second was another story. By the time the bank was completed, construction costs had mushroomed to $80 million, the largest change order coming from Carson, who added two floors to the original design.

Another factor in the rising costs, according to McGee, was Richard Meier, the noted architect. “It was Richard’s first commercial office building and the nature of his architecture is him. His precision and design are unique.”

Meier was still revising plans as the building was going up. If he saw an unexpected light pattern, he would enhance it, add a skylight or change a wall to open the view. This led to some expensive change orders and oftentimes, stress between Meier and the builders–Hines Construction and Turner Construction.

“He has a world-class challenging personality,” according to McGee. “He’s also a great architect because he forces people to view things differently.” On occasion, both the Hines Construction people and McGee ended up negotiating with Meier to blend his vision with the realities of construction.

Carson and McGee made decisions on the building project that ran from the mundane to the bizarre. On April 23, 1987, a half-completed Bridgeport housing project called L’Ambiance Plaza collapsed into a contortion of twisted steel and concrete after a jacking mechanism slipped. Construction crews working the People’s project just blocks away rushed to the aid of victims. When it was over, 28 workers were dead.

In the aftermath of the L’Ambiance accident, engineers working on the Bridgeport Center project became super-wary. Ordinary things suddenly required decisions from the chief executive, including the size of the bolts needed to lock the granite to the building.

Carson recalled in an interview in 1993, “Three types of bolt were available for the process: The first bolt that could do the job cost approximately 20 cents a bolt and had a lifetime of 50 years. The second bolt was made of another kind of metal. It cost 50 cents a bolt and lasted 100 years. And then, they said, there’s an ultimate lifetime bolt. It will be here through eternity. The engineers said we can only give you the specifications; the choice has to be yours. This was pushed all the way up.”

That’s how tense people felt at the time. Carson picked the 100-year bolt. But that was not all. They asked about wind tolerance. Did Carson want the building to withstand hurricane winds of 150 miles per hour? How about 300-mile-per-hour tornadoes?

McGee found many decisions were easy to resolve after a quick discussion with Carson. The 16th floor, which housed the executive offices, was a case in point. Carson placed his office on the city side, away from the lofty views of Bridgeport Harbor and Long Island Sound.

“He wanted to look at the people,” according to Ed Bucnis, an executive vice president whose office was across the hall. Carson wanted to see activity and view the city to which he was so committed. He also placed the board room at the opposite end of the floor, eliminated executive bathrooms and suggested that the executive dining room be a small place to have a snack or hold a meeting. A terrace was located just outside, but was infrequently used because, at that height, the winds off Long Island Sound turned out to be surprisingly fierce.

Carson had correctly predicted the need for the close integration of computers and bankers. Most financial institutions located their operations units in remote (and less-expensive) places. It was during the planning period for Bridgeport Center that Carson announced every employee would become computer literate. He also made the decision that the new building would contain computer operations.

Carson made many functional decisions, but the look and feel of the bank was Meier’s, including one of the most dramatic atriums in the country. The 18,000 square-foot room with its white walls, multiple balconies and fabulous glass ceiling, would become a well-recognized site in magazines, newspapers and fashion publications. Once, it also served as a temporary home for several valuable Alexander Calder mobiles owned by a private banking client.

The appeal of the atrium was not so much its size, as its constantly changing light patterns, colors and shadows. In the morning, there was often a peach tone. In the late afternoon, blues became dominant. To see the atrium on a sunny day, with intricate shadows defining its soaring white walls, was to understand how nature’s beauty can be brought inside a building.

“The building is Richard Meier,” according to Carson from a 1993 interview. “The fascinating thing he did was that he worked with all our people on things like the main banking floor. He asked them questions like, ‘Where do you want people to go when they come in?’

“The way the building looks is his. I would not allow anyone to change the look of anything. If you’re going to hire a world-class designer, you have him design the building.”

Meier felt the same way about Carson. “It is rare for an architect to have a dialogue with a client as I did with David. He was great … involved and opinionated, but open and receptive. We worked well together and were able to match up against a very demanding schedule.”

At first look, Bridgeport Center’s interior seemed sterile. The 150-foot curved granite teller counter, for instance, could be compared with the endless counters at an airport terminal. And almost everywhere, it was white. And where it wasn’t white, carpets and cubicles were gray. This reflected the overwhelming Meier religion of white, his signature look.

But creative geniuses develop ideas as they work. One day, as the building neared completion, Meier called Carson to set up a 6 p.m. meeting at his Manhattan office.

Carson arrived, visited a bit, and Meier brought out the floor plans which he had marked with colored pencils. Some columns and walls were designated for painting in primary colors. Carson and Meier poured over the drawings for a couple of hours, agreeing this would add another level of excitement to the building. Then they adjourned to the bar at the Four Seasons to celebrate with wine and dinner.

About 10 a.m. the next day, McGee received a call from Meier’s chief designer: What were Dave and Richard doing last night? He wants us to color it!

According to McGee, “Meier’s staff assumed that all the interior walls would be white. Meier had a very specific formulation of white that had to be specially mixed to get the right shade. The white had to have a precise amount of violet in order for the white to be right. At the time, the effort to create the perfect white drove me nuts. However, when the painting contractor finally produced the perfect white, I have to admit, it really stood out. The sharpness of the color was noticeable. The funny part of all this focus on the perfect white, was that having achieved the goal, Meier decided Bridgeport Center would be the project where he would experiment with color.”

Sandra Brown, the bank’s corporate secretary, had her own take on the architect’s fondness for white. “For Meier, who was into white, the people added the color.”

In fact, Meier picked some incredibly vivid colors for a few walls in the building. The operations area, which housed the mainframe computers and other technologies, had very few windows and a few bold walls of royal blue, kelly green and purple. Directions such as “turn right at the bright blue wall,” were not unknown to visitors in this labyrinth inner sanctum. It was significant that Meier wanted to improve the ambiance of the computer floors, which had almost no windows, by the use of color in the hallways.

There are tales, too, of the day Richard and David chose the art collection for Bridgeport Center, the two spent hours at Viart, a New York City art gallery, doing a thumbs up or thumbs down as they chose collectable photographs, almost all of them black and white. The entire collection had one criterion, both men had to like the piece.

Choosing places for the art obviously added fun to the project. Accounting, on the 15th floor, received valuable, but thought-provoking photos from the Great Depression. “Wave,” an incredible Russell Munson close-up of water in action, was placed near Operations. Residential Lending got the “Brooklyn Bridge,” of course. Also in the mortgage department was a small print of what appeared to be a dead pachyderm collapsed on the road. In reality, this was a photo of an “Exhausted Renegade Elephant” being washed down with cooling hoses after a mighty escape. It received some employee complaints, requesting a scenic photo–not a newsworthy one. The art work stayed.

Telephone Banking had the most controversial art, however. The 11th floor, where the call center was located, featured famous portraits. Poster-sized head and shoulder shots of Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, Marlene Dietrich and Anna May Wong were in the entry foyer. The way Anna May draped her dress, however, showed more breast than shoulder. Receptionists working at the main desk complained about Anna May’s super-sized bare breast–directly facing them. The framing was moved to a less obtrusive location.

Paint colors and artwork were chosen as the building was in its final throes of completion. Near the end, Carson made the decision that there would be no more structural modifications. Turner Construction would have no further change orders, and would have to complete the process on time or pay penalties. Construction continued at a furious pace and Turner delivered.

McGee managed to keep his sense of humor through the arduous building process. When the building was finally completed, he hosted a rattlesnake dinner for the union workers, many of them southerners.

“Carson gave Bridgeport a sense of beauty,” according to McGee. “It’s an example of the bank setting a standard built around quality and design. He took a risk and pulled it off.”

The employee reaction to Bridgeport Center would be tricky. Staff at People’s was loyal and hard working, but an eclectic bunch. At the technology site on Park Avenue, employees wore jeans and reheated their bag lunches on site.

Branches had more formal rules. And in the former headquarters building, the dress code was corporate, but the offices were a mish-mash of aged and new furniture with lots of plants, pictures and knick-knacks. Water coolers were a mainstay. And secretaries made endless pots of coffee for all.

Peter Brestovan, first vice president, Real Estate Services, was charged with the challenge of managing the move-in because his domain was, and would continue to be, maintenance and operations of all People’s facilities.

“At the time Bridgeport Center was built, People’s was operating at ten addresses in the city. We didn’t want to bring the sins of ten buildings down to one,” Brestovan related. “We needed one culture, one way of doing things.”

He set up a “culture committee” with Marianne Gumpper of Human Resources, and a bevy of bank officers. The group made some tough decisions. Dress codes were upgraded. Water fountains–with city water–replaced the bottled water coolers. Coffee pots were out.

Bridgeport Center would have a central snack bar and full-service cafeteria. To support these facilities, operated by outside vendors, departments would not be allowed coffee pots or refrigerators. (Telephone Banking, the giant call center with dozens of workers and a tightly maintained break schedule, would get its own facility.)

Most shocking was the switch from a rabbit warren of offices to open space cubicles manufactured by Steelcase. Only vice presidents would have offices, and each title and grade level had a prescribed square footage, according to rank: vice president, first vice president, senior vice president or executive vice president. The basic vice president offices were pretty small, and so were the precisely picked desk, credenza and one allotted bookcase. No variables were accepted for the type of work done, or space needed to do it, in these cubicles and offices. Changes were not allowed for one year.

The Culture Committee had its work cut out. A Move-In Team was created, with representatives from every department. The team met regularly to discuss issues, view plans, see the cubicle mock-ups and gather facts to share with fellow employees.

Pack rats would not be welcome at Bridgeport Center. Important records needed to be archived–and the rest thrown out. Brestovan talked to Larry Parnell, now first vice president of Corporate Communications and Investor Relations, whose creativity and sense of humor were legendary. Parnell’s staff pulled together a comprehensive marketing plan, including everything from a Big Blue Day with events at the construction site (and blue ice pops for all), to a Grand Opening with popcorn, clowns and Gov. William O’Neill. But the department’s most memorable achievement was “Filebusters,” a video takeoff on the popular movie “Ghostbusters.”

Filming was done at the old headquarters, using real people and lots of paper. As a matter of fact, Dave Driscoll, a marketing department manager and good buddy of Parnell’s, brought in his leaf blower to help papers zoom around the offices. A band of employees danced and sang a chorus at the Austin Street Warehouse, where serious paperwork was to be filed. And people throughout the organization were filmed dumping file drawers and sticking paperwork in zany places … all to the catchy tune of the newly minted People’s song: “Filebusters.”

The move-in was a success. People’s employees, who lived in traditional ranch houses, Cape Cods and colonials, adapted fairly quickly to the stark, but beautiful, nature of Bridgeport Center. Pride replaced concern. Carson added intriguing art to the executive floor. A Zen-style grouping of dominant red and black wall art, juxtaposed with tiles and smooth stones on the carpet, created a war-and-peace symbiosis in the reception area. And on the wall opposite the reception counter, a simple vase held an immense bouquet of black and white silk flowers. Both pieces were created by award-winning artist Jan Hertel, a friend of Carson’s and wife of one of his college fraternity brothers.

In his office, Carson also proudly displayed two large framed montages from Meier. The groupings were a mixture of red, white and black building sketches and specifications for the building. Meier had now spent many months working closely with Carson. Both were delighted with the final result. Meier later described his gift as “abstractions of the aspects of the design of Bridgeport Center, something I thought spoke of the collaboration we had.”

When Meier received a Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects, his friend David Carson gave one of the two nominating speeches. Carson was also an honored guest in 1985 when Meier received the Pritzker Architecture Award, viewed as the Nobel Prize of architects.

With the success of a new building, Carson had other issues to address–including what would be the greatest challenge of his career.

I though I was reading Hemingway’s book In Our Time. Lennie, thanks for the short vignette, that was great!

“People’s employees, who lived in traditional ranch houses, Cape Cods and colonials, adapted fairly quickly to the stark, but beautiful, nature of Bridgeport Center. Pride replaced concern.” Those two sentences are totally management public relations. I worked at People’s during that period of time, and know many of the employees did not like working at the building. I worked on the 5th floor, which was huge, sterile and often very drafty. Working in a completely white and grey environment broken up by a myriad of cubicles with almost no natural light if one was seated was not a pleasant working environment. The coffee bars often had long lines as there were very few of them. The cafeteria was quite nice, but there was no refrigeration available for employees who wished to brown-bag it. The interiors were unfriendly and the main banking floor really did have all the charm of an airport terminal, but the building as a whole was and still is most definitely an imposing sight and makes a great skyline for the city.

I remember both the implosion like it was yesterday and the ribbon cutting. David Carson was definitely a hero in the City not only at the helm of People’s Bank but his consistent support of the University of BRIDGEPORT. I credit former Mayor Thomas Bucci for both the People’s Savings Bank Headquarters as well as the former Wright Financial Center.

The Richard Meier building was definitely an architectural work of art. I was not pleased with the exterior white materials that consistently make the building look dirty.

Lennie, this was a good read. You really capture the moment. Your Bridgeport book has been on my coffee table for over 25 years. I will have to get a copy of this book. Good luck with it!

Both buildings were not only architectural landmark buildings but were also the last time this city had any major development.

I also remember Chris Caruso being one of the lone council members to vote against any tax breaks for the Wright Financial Center. It is so hard to believe it is 25 years Bridgeport has been stagnant. When you think of how far the City could have gone in the 10 years Ganim stifled the City. Very very sad. Thomas Bucci may be remembered for the financial review board but also for being a key player in two major downtown developments that would have been welcomed in Stamford.

Lennie, who wrote this, John Marshall Lee? 🙂

I’m sure Carson wishes it was his 25th birthday on the 80th Anniversary of the People’s Bank Center. What I would like to hear from Carson before he passes on is: How did People’s Bank know the real estate bubble was going to explode not too long after the bank sold their real estate portfolio? What were the economic indicators that led to such a magnificent financial move? Happy 25th Birthday, Mr. Carson.

What’s interesting about this is they sold the toxic mortgages and kept the good ones. I can picture all the top People’s Bank officials huddling in front of the 16th floor office windows facing Bridgeport, soon after the attorneys signing the purchase of the toxic mortgages left the room. And on the count of three, all saying, “suckers!”

Joel, you can read all about it in Bow Tie Banker. I shall present you a copy. Your only requirement is a book report. Oh boy …

I purchased the book and David Carson signed it. I asked him the question about the real estate portfolio sale that day and he just smiled.

“It is so hard to believe it is 25 years Bridgeport has been stagnant. When you think of how far the City could have gone in the 10 years Ganim stifled the City. Very very sad.”

Steve, what’s sad is how some people write ignorant comments and they really believe them themselves. Ganim left office about 11 years ago for one. When he left, there was about $52 Million in the City’s rainy day fund. We had 10 years of no tax increases of which you benefited if you had the homes you owned back then. The real stifling of the city began after Joe Ganim left office. Those who did the stifling and got away with it are still in office and even gone to higher office. After Ganim, the city, state and federal government has been getting stifled by the same people who set up and conspired with Ganim. Joe Ganim signed off on what council committee chairs and the city council put on his desk. Joe Ganim wasn’t the only one convicted and many were not indicted and some cut deals with the feds to give them what they needed to catch the big fish they wanted. It’s been over 15 years since the feds started their probe and they still refuse to release all documents relating to the corruption probe. Why is this? When or if ever released expect a bunch of black marks covering every page. The feds refuse to release documents relating to the probe because it’s an on-going probe. None of those convicted are currently working or doing business with the City of Bridgeport. Maybe they’ll decide to release them when or if Joe Ganim runs for mayor again. If that happens, expect only details that hurt Joe Ganim to not be blacked out. Run Joe Ganim, Run!

Joel Gonzales, you are an asshole. Joe Ganim has ruined the city’s reputation and was a thief. I thank G-d every day I do not work for the City under his rule and even more grateful he personally separated me from the City. I have his personally signed letter framed. No individual with half a brain would put money in his campaign unless they use their money to wipe their asses. You would have to hate Finch unbelievably so to put a criminal at the helm when Bridgeport is about to take off. I would work my ass off and personally knock on every door to guarantee Ganim’s dream of a political comeback never comes to fruition. He is toast. Sorry Joe, I believe in second chances and I believe you put in your time. I do not believe you deserve to even kiss Bill Finch’s ass. As long as you have Joel Gonzales and Ernie Newton singing your praises, I think you are capable of reading the writing on the wall. I actually believe if Marilyn Moore were more aggressive speaking about Bridgeport economic development, her eloquence alone would leave you in the dust. John Fabrizi, Mary-Jane Foster, Chris Caruso, John GOMES, Michelle Lyons, George Estrada, Carmen Lopez, Charlie Coviello, John Stastrom, David Walker, Andres Ayala, Max Medina, Ted MEEKINS, Darleen MEEKINS, Mike Marella, Phil Kuchma; honestly, the list could go on and on. Why would anyone support Joe Ganim? He may be a nice guy as most politicians are, but a leopard never changes his spots and the history books will never speak well of Joe Ganim unless it is written by Lennie Grimaldi. It is a shame really. Joe Ganim had so much potential. He really screwed up his political career. I believed he could have gone really far. Bridgeporters may not be the most sophisticated voters, but they are not dumber than a box of rocks either. I think they’d take a pass on Joe. So Run Joe, Run!

“Joel Gonzales … you are an asshole.”

This only mean one thing–you love me.

I do, Joel.

You have a few “leopards” on your list of better mayoral candidates. The best thing you did was not to go on and on with the names. Andres Ayala? Really? He left the council presidency to serve as State Rep. in the 128th. Soon after, Bill Finch gets elected and is left holding the empty city bank account and additional debt. Finch hasn’t done any better. John Stafstrom? Really? The former city councilmen who negotiated to remain as the City’s Bond Counsel ’til this day? The one who assured the Ganim administration the pension plan he put together was a win-win plan for the city? I can go on and on as I was there (on the city council) for six years. You are a disgruntled former city employee mad at Joe Ganim for firing you. I’m sure that was among the many good decisions he was advised to make.

Disgruntled city employee? Nah. I served Mayor Moran and got my life back after she lost. There is a huge difference between being a city employee and serving the City as a patronage job. On stage 24 hours a day. Every council meeting, every public event, every fundraiser. I had to join a gym in Milford just to get away from all the annoying needy people who had to just speak to the Mayor about pure BULLSHIT. I do not blame Ganim, though it was a pretty stupid move to get rid of the city’s biggest cheerleader. I was MORAN’S biggest supporter, I was not that naive. I blame Ganim for becoming a megalomaniac. To actually believed he could get away with it. He became an embarrassment to his family and friends and to think he believes he can get reelected, well that just goes to show he really has balls.

This project started under Mayor Paoletta and was administered by BEDCO, as part of an eminent domain action.

In interviews I conducted with bank executives, including Sam Hawley and Nick Goodspeed, the decision to build a new headquarters was made while John Mandanici was mayor, but many of the details had to be sorted out. By the time Carson joined the bank several years later, Paoletta was mayor and he certainly embraced the project, but from all my interviews for Carson’s biography and an oral history I did on behalf of the bank, the project was corporately driven. Ultimately they said it was Carson’s decision to shepherd the project and decide where it would be built. Carson, if he so chose, could have built the new headquarters outside the city. He decided he wanted it in Bridgeport continuing the tradition of a bank deeply rooted in the community. The current bank leadership by comparison shows a significant disconnect from the city.

Lennie, can you give me some financial advice? I have a pretty penny with People’s Bank. Should I invest it in my city as opposed to where People’s Bank is suggesting I park my money? How can I invest in my city if the city is as disconnected from us as People’s Bank is?

Hour-Back was trying to give your former boss Bucci credit for this project. Ellis-Adams was a great corporate Bridgeport and Bridgeport citizen.

Lennie, the original plan was to build a computer operations center. My recollection is the pressing need to consolidate the various downtown locations and available funds from high mortgage rates in the early ’80s led to the decision to build a new headquarters. Don’t forget, there were rumors it would be built in Shelton.

This article is an excellent read. Unfortunately, it is a bit depressing. From this article my takeaway is the People’s United Bank building was the last major development in Bridgeport. From this development, Bridgeport could have become the financial powerhouse that Stamford hoped to be. Instead, we had no further development beyond this building. It is sad.