Charles Brilvitch is a Bridgeport treasure who spent decades marinating in the city’s architectural history, something that requires endurance, passion and love for the things that often go unnoticed. Charles put the work in. No one on the planet matches Sir Charles for his depth of Bridgeport bricks and mortar and the stories behind the stories.

What’s the reason behind that street? Why is a name attached to this building? Why is a city high school called Bassick?

Bridgeport has transformed the face of its public schools. A new Harding High School opened this year, Central High underwent a major face lift. Bassick High, along Fairfield and Clinton Avenue, is next in line.

Board of Education members are pondering the future use of the Bassick building, a majority of the projected $115 million improvement financed by state dollars. Knockdown and rebuild?

School board member Maria Pereira supports a hybrid overhaul: preserve the original building from 1929, demolish the 50-year-old addition for a new structure, in lieu of a complete knockdown on the site.

Pereia has started a petition drive, see here to build support.

Brilvitch, in the commentary that follows, makes a case on behalf of architectural restoration.

Bassick High School is a building that deserves to be preserved. It is a masterwork of Neoclassic architecture from an era that many consider the absolute pinnacle of American design prowess, building craftsmanship, and materials availability. It is an historic landmark that has been an object of immense civic pride in years past and, with appropriate restoration, could return to its iconic status for many generations to come. And it is without doubt eligible for inclusion in the State and National Register of Historic Places, a status that makes restoration not only eligible for special grants funding, but also the Connecticut Historic Tax Credit (25 per cent of construction hard costs), which can be syndicated to investors to significantly enhance the restoration budget.

The long-term wisdom of retaining monumental works of civic architecture can perhaps best be illustrated in New York City: In the 1960s, it had two grandiose early-twentieth-century railroad terminals, Pennsylvania and Grand Central Stations. In that time period, both were considered expendable “white elephants” that were described as functionally obsolete and out-of-sync with the needs of a dynamic, up-to-date city. And so Pennsylvania Station–designed by the celebrated architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White and modeled on the Baths of Caracalla in ancient Rome–was demolished; its irreplaceable marble columns, mosaics, and statuary were hauled off to a landfill and the site given over to utilitarian glass-box office towers and a banal new Madison Square Garden. Grand Central, on the other hand, escaped demolition and replacement by an office building by a hair’s breadth. It survived to be restored in our time to its original glory, recognized now as one of the most important landmarks in the entire nation and a testament to the wisdom and sublime taste of its designers. Penn Station and its “functional” replacements, meanwhile, are universally derided as one of the great debacles of twentieth-century urban planning. The glass box office structures and arena that replaced it look tired, cheap, and dated and collectively point an accusatory finger at those who foisted this so-called “improvement” on a remorseful city.

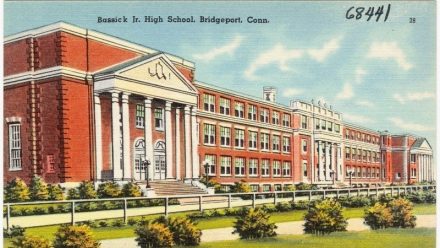

Bassick High School, too, dates from the Beaux Arts era and the corresponding “City Beautiful” movement that brought classical majesty and grandeur to America’s burgeoning cities. The great pillared portico at the center of the building echoes the forms of the Arch of Constantine in Rome, trimmed and quoined in the choicest Indiana limestone, an entryway designed to inculcate the student or visitor a sense of the importance of the learning that goes on within. The portico is surmounted by carved stone urns and a stone balustrade at the roofline. This central pavilion is flanked by long classroom wings that transcend the ordinary with heavy stone lintels distinguishing the second-story fenestration and a water table delineating the third story as a proper classical entablature. The flawless symmetry of the facade terminates with projecting pavilions that echo the forms of the Roman Pantheon of the 2nd century AD with their porticoes supported by Corinthian order columns. The colossal scale of the facade, the richness of its detailing, and the exquisite perfection of the design is kept almost secret from the city that surround it: uniquely, the building is set at right angles to the busy thoroughfares that flank it at either end and has its face to a private courtyard dedicated to its use alone.

Bridgeport in the 1920s was one of the most progressive, avant-garde, and well-to-do cities on Earth. Its housing was a model for the rest of the nation. Its industry was cutting-edge and set the standard everyplace else strove to keep pace with. And it had a cadre of world-class industrialists determined to show the world what a manufacturing utopia could look like. This high-minded civic leadership did not live in gated enclaves far removed from the businesses they commanded–witness the opulent mansions of Clinton Avenue, cheek-by-jowl with the three-family tenements of the workers the owners employed. Many of the industrial moguls felt a strong connection with those whose livelihoods they provided, helped them climb the ladder of success, and shared their aspirations for the up-and-coming generation.

Such a man was Edgar Webb Bassick (1872–1948). Bassick was president of the Bassick Company, world’s largest producer of furniture and automobile hardware (it was noted in 1929 that Bassick paid out almost $2,000,000 in salaries and wages to his employees, nearly all of them Bridgeport residents), and chairman of the board of directors of People’s Savings Bank. He had the wherewithal, the drive, and the unbending desire to make his dream a reality: a memorial to his father in the form of the most beautiful, state-of-the-art school of higher learning yet seen in America on the site of his family’s historic Fairfield Avenue estate.

Edmund Chase Bassick (1834–1898) led a life worth commemorating and most worthy of imparting life lessons to young people. Born into poverty on the coast of Maine, Bassick was shipped out as a crewman on a sailing vessel when barely into his teens. Travelling around the world, he found himself stranded in far-away Australia at the age of 16. By a stroke of luck the teenager discovered the very first gold on that continent, and is single-handedly credited with precipitating the Gold Rush of 1851. Bassick took his fortune in gold and made his way to the coast, hoping to find a ship to take him back to his homeland. When nearly there he was attacked and robbed of everything. Undaunted, he made his way back to the goldfields and amassed a second fortune. But again he was robbed, beaten, and left for dead. This cycle of events was repeated a third time, at which point he threw up his hands and gave up on the Land Down Under and its population then largely comprised of ex-convicts. Penniless, he secured a position as a ship’s crewman and eventually made his way back to America.

Twenty years later, “Hard-Luck Ned” had acquired a wife and young daughter and was again living a hand-to-mouth existence as a prospector in a one-room cabin in Custer County, Colorado. One day out of the blue some familiar-looking rocks caught his eye. Bassick quickly bought up the mining claim to that remote piece of ground for a pittance, and in no time found himself sitting on top of the largest gold mine ever discovered in America. With his first rush of income it was noted he bought himself 20 tins of sardines, and sat eating them with his penknife just outside the general store. Soon, however, Bassick opened a mammoth supply emporium, where goods were given away at half their wholesale cost to the entire district. The man who had known so much misfortune was determined to share his sudden wealth with others.

Within a few years the fabulous Bassick Mine was sold to big-time investors for a fabulous sum, and Edmund Bassick returned East to retire in style. Searching up and down the coast for the most beautiful, advantageous spot, he set his sights on Bridgeport, Connecticut, fairest-of-the-fair in all of New England. Bassick purchased P.T. Barnum’s former home, “Lindencroft,” on what was then “Millionaire’s Row” on Fairfield Avenue. Renaming it “Miner’s Rest,” he added greenhouses and gardens to the estate to engage his passion for horticulture. And, always mindful of his origins, he built a development of model workers’ cottages along Bassick Avenue, named it Bassickville, and rented the houses out for a pittance to those striving to get ahead in life. It was said he donned overalls and work gloves and personally landscaped each of the houses.

Bassick died in 1898. By the time his wife died in the 1920s, the Victorian mansions of Fairfield Avenue were being abandoned by the wealthy and replaced by apartment houses, funeral homes, and Moose lodges. Edgar Bassick did not want to see the home of his youth degraded for use as a rooming house or worse and decided to turn its site into a civic asset for the city that had been so welcoming to his family. A great school, he felt, would do honor to his father’s name and would continue the Bassick family tradition of helping those who help themselves. Spurning men of lesser abilities, he selected as his architect Ernest G. Southey, a man whose eye for design had earned him a place at the very top of his profession in Southern Connecticut. Working together, the two men created a vision of the most beautiful school of higher learning ever erected in America, an edifice that would serve as an example to the rest of the nation. And in that they succeeded.

In recent years Bridgeport has embarked on a program to revamp its educational infrastructure, to demolish its old school buildings and replace them with modern “state of the art” structures at tremendous expenditure of public funds. The reasoning often stated is that retrofitting old structures is problematic for architects and contractors, and that it is much more efficient to start with a clean slate and to build from the ground up. The inference is that the city’s habitually low test scores are the fault of the buildings themselves; that it is next to impossible for students to learn in “antiquated facilities.”

Let us consider for a moment the Yale University campus in New Haven: Yale has buildings that date back as far as 1750, and the vast majority of its building stock was erected in the teens and twenties of the last century. No one would THINK of tearing any of these hallowed, venerable buildings down and replacing them with glass-and-concrete boxes that look like prisons. They are Yale’s identity, Yale’s tradition, Yale’s trademark to the world, irregardless of the fact that they may have auditoriums with level floors and that retrofitting HVAC systems might be “problematic” for tradesmen. And the illustrious exploits of Yale’s alumnae seem to prove that learning is indeed possible in a building that was not constructed yesterday.

Bassick High School is an eminently beautiful structure, in sound condition, made of materials that are irreplaceable or prohibitively expensive in our day and age. The school has witnessed the coming-of-age of generations of Bridgeporters and has acquired a patina and a tradition that cannot be reproduced at any cost. It is a landmark that Bridgeport should be most honored to possess. Its demolition is unthinkable.

Thank you, Charles Brivlitch for this masterpiece detailing the history of the Bassick family and it’s noteable contribution to Bridgeport.

If you have not already done so, please consider signing onto the “Save Bassick High School” petition and post a comment detailing why you support its preservation.

We are asking only Bridgeport residents, current/former staff, and current/former students to sign on.

The Bridgeport Board of Education will be discussing and voting on whether to demolish the entire Bassick campus or to completely renovate the original Bassick building while denolishing the 1968 addition and replacing it with a new structure.

We can provide a state-of-the-art learning environment by installing all the latest technology, machinery, etc. without demolishing the most beautiful school ever built in Bridgeport.

The school board meeting will be held at Aquaculture School on Monday. You should arrive by 6:15 PM if you would like to sign up to speak for two minutes.

I hope we can come together to save this incredibly beautiful and architecturally significant structure.

I love History and that was a great history lesson from Charles Brilvitch. Thank you,Mr. Brilvitch and, thank you Lennie, for providing this forum for that lesson. Now I really want to see the inside of Bassick High School(the parts that we are talking about) and maybe more members of the Bridgeport Community can be given a tour as the ‘new” Bassick is being planned.

Maria, I can see preserving the original building, I haven not been in Bassick so in don’t know any of the architecture significance it has inside, if any. If it’s all just about the exterior how will the other building complement it. As of know it’s just sandwiched between a single street. If is just about the exterior architecture. Why not just savage the front exterior and replicate on the in the other side of the completely new school. Where it can be seen and admired. At the end of the day, like school uniforms that seemed to take forever and implement, in my opinion and could have been stronger, education is not a fashion show. you don’t want bells and whistles. What you need is an optimal learning environment. But I do like the building. I say two corridors on each side of the original building that connects the new building with and open court yard, with the facade to complement the original Show me the plans, not just an Idea.

have, not

I don’t

now,

replicate it on the

if it’s just,

replicate it

to implement

an open,

No building architect going to these problems. #ESL 🙂 Maria, who’s the architect? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHZl2naX1Xk

help with 🙂

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LN8EE5JxSGQ

Excellent!!!

Charles Brilvitch for Mayor!

We will not be doomed by history repeating itself.

One of the most fascinating pieces of Bridgeport history that I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading — written in some of the most elegant prose used to accurately portray history that I’ve ever encountered…

Terrific stuff. Congratulations, Charles! A true “masterpiece” (per Maria Pereira)…