Billy Chase talked often about getting his life back, but he never really knew what that meant.

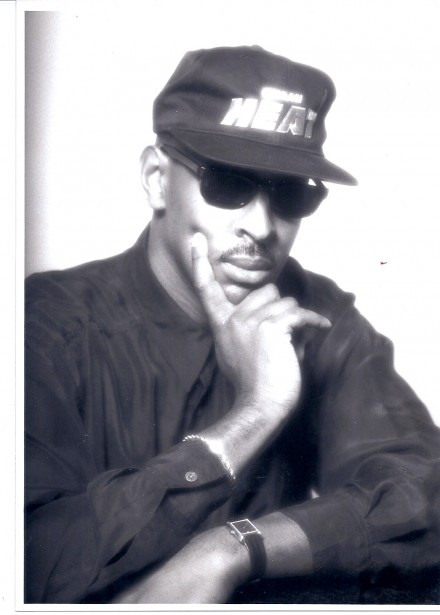

Chase was a complex study. He was engaging, idealistic, kind, funny, and had an uncanny gift for gab that aided him in his dangerous police undercover work. He had the ability to talk trash on the basketball courts of the inner city or walk into a court of law as a lucid law enforcement witness. He could be almost anyone he wanted to be. But he had an intense side too, that segued from bright light to darkly sardonic. We all fight our demons. For Chase demons often came at rapid-fire gargoyle intensity. Sometimes he could not quiet his brain, it was like a Ferrari at full throttle. He had difficulty sleeping and when he did nightmares came fast and furious.

I did not know Chase in his childhood. He was raised Catholic, third in a family of six children, in a Bridgeport with few black Catholics. He attended all-white parochial schools and church at St. Augustine’s Cathedral where he sang in the church choir and was an altar boy. Billy’s dad William Joseph Chase Sr. was the product of a bi-racial marriage that included African American, Seminole and Cherokee Indian. Billy’s maternal grandfather, born in Ireland, moved to Florida at a young age where he, a white man, fell for a black woman attending a black high school, which generated attention in the segregated south. After graduating nursing school in Augusta Georgia, Billy’s mom Nellie encountered racism at the Florida Hospital where she was employed.

They had a friend who worked for General Electric in Bridgeport, a factory town with a reputation for jobs. Nellie became the first black registered nurse at St. Vincent’s Hospital. Billy’s dad worked as a machinist foreman at the Bridgeport Brass Company. They began raising a family in Bridgeport in the 1950s.

I met a 34-year-old Chase after he was forced to retire from the Bridgeport Police Department as a young man. When the heat is turned up usually it’s the bad guys who leave town. What happens when the hunter becomes the hunted?

When witnesses have information to put away violent criminals the federal government, at least, has a program called Witness Protection. There was no such program for retired cops. Following death threats and a serious attempt on his life in which his apartment was shot up, Chase retired and left for Florida where his parents had returned.

A newspaper article in 1993 about Chase’s departure caught the eye of New York literary agent Frank Weimann who had asked around and thought I could be a fit as a result of my journalism background and knowledge of the underbelly of the city, writing Chase’s story. I had heard about Chase in the mid 1980s as a young staffer for then-Mayor Tom Bucci. I only knew Chase was a deep city undercover working cases for state and federal law enforcement. Bucci had urged the help of the federal government as mayor to take down major drug gangs terrorizing neighborhoods. Weimann had agreed to represent us in finding a book publisher but first I had to meet Chase.

Visiting him in Florida, Chase was tall, a sinewy 6’4 externally, but he was a young man with an old body broken from fights with crackheads. His medicine cabinet was crammed with pain killers, his large hands swelled from damage. Parts of his body were worthless for the most mundane actions. He was trying to rehab his body with numerous swimming exercises. If his body had betrayed him it was nothing, he said, to the betrayal he felt from a law enforcement system that had chewed him up and spit him out. He felt like a human missile pointed in one direction to take out the bad guys with no safety net when it was over. It was a life of aliases walking among minefields and trapdoors.

Chase lived meagerly on a small police pension. He wondered if a book could make money. I told him him few books make money, they are often a labor of love. Still, we agreed to work together. We knew a lot of the same people. We connected. I realized, book or not, this guy was going to be a friend. I spent an intense week interviewing him in Florida. I also needed to learn Chase-speak.

“How ya doing,” I’d ask.

“I am chill,” he’d respond.

In the warmth of the Florida sun it did not seem “chill” to me at all. I’d look at him quizzically.

“No, chill is good,” he’d say. “It’s like being cool.”

“So chill equals cool equals calm?”

Chase took pity on me with a laugh. “You’re catching on. You Italian guys can sing but you can’t rap.”

It hit me, this was the first time I had to write something from the perspective of a black man. What does someone know about being black unless you’re black? So I did the next best thing. I marinated in everything Billy Chase: the food he ate, the music he played, the books he read, the people he admired, the things he liked and disliked.

To help me along in the project Chase had a goldmine of information from the cases he worked–drug gangs such as The Number One Family, the Cats and Rats and Terminators, the Dicks brothers–including transcripts of when Billy wore a wire. Chase also had gone where no black undercover had gone before, infiltrating a drug faction of the Gambino Crime Family. Chase had a communication skill set that allowed the color of green–money–to transcend his skin tone to cynical mobsters. The subject matter was also a sweet spot for me because I had chronicled organized crime families as a young reporter.

During that week of interviews Chase puked up a reservoir of emotional toxins in his system. I recorded each segment and then transcribed them.

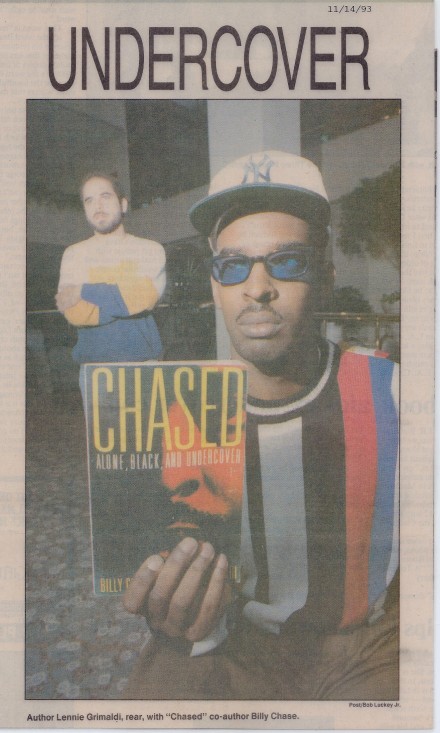

A book proposal was written, most publishers took a pass but Weimann found a home for it with New Horizon Press, a small house in Far Hills New Jersey that specializes in uncommon heroes. In the spring of 1993, the publisher and editor Joan Dunphy had one of those good news/bad news offers. I want the book, but I want it filed in 90 days, she ordered, to meet the fall holiday season. The project was pretty much around the clock. As a goal I wrote 1000 words a day until it was done. But it wasn’t really done as far as I was concerned, in some areas the manuscript was rushed and sloppy but a deadline is a deadline is a deadline. She accepted my title for the book Chased but she added a kicker, Alone, Black, And Undercover.

In the fall of 1993, Chase and I promoted the book together. He decided to show his face within reason understanding if he wanted his story to gain traction he had to talk about his life to Connecticut media outlets. His departure from the police department was still somewhat fresh and some drug dealers had long memories. In Florida he had assumed a different name, but back in Bridgeport he was extremely recognizable. We met with reporters only in areas he felt comfortable. He always packed a weapon, just in case.

The Today Show wanted to do a segment with Chase. We entered the green room of NBC studios in Manhattan. Geraldine Ferraro, the first female vice presidential candidate to run on a major party, was slotted before Chase. When he was on his game Chase could gab about any subject to any person. He noted her accomplishment from 10 years prior, albeit it a losing effort with Democrat Walter Mondale in the Ronald Reagan landslide of 1984, and she took an interest in his unique undercover work. She had as many questions for him as he had of her.

“Be careful,” she told him.

“Well, how about signing my bulletproof vest?” he asked her.

Chase opened up his shirt, displayed the vest and she accommodated him with a Ferraro autograph.

Thursday afternoon, in a fit of tragedy, Billy Chase gave up being careful … forever.

This is an incredible story. It is a uniquely “Bridgeport” story as well as a uniquely American story. There is much to learn from this story and its tragedy.

*** Paranoid, lonely, distrusting of strangers and seemed not really a happy soul at times! Maybe even a victim of his own law enforcement circumstances from the past, no? ***