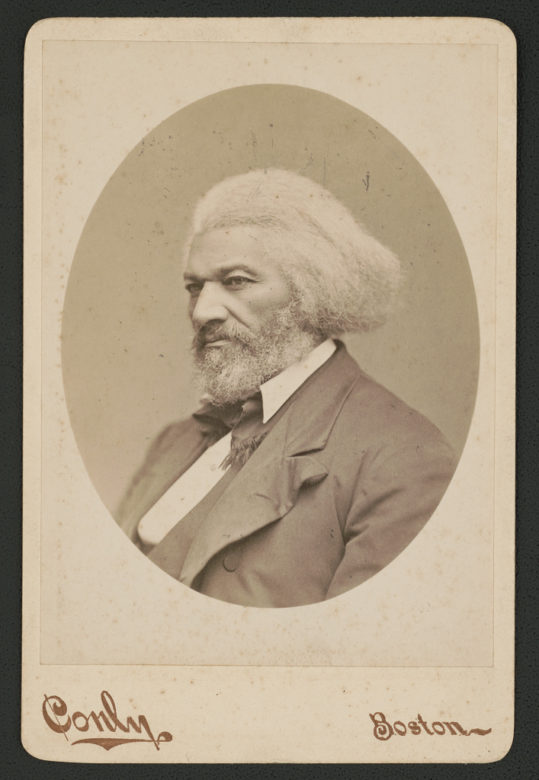

Have you pondered historical figures you’d crave to meet and transport them decades and even centuries for an assessment of their contributions and legacies? How about putting together the soaring oration combination of Abraham Lincoln and born-into-slavery-abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass? They had a complicated relationship.

Can you imagine the dialogue given the current state of affairs in a country still torn on race?

In 1852, Douglass gave what is now his best-known speech, lamenting the state of American racial inequality: “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?”

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham … There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.4

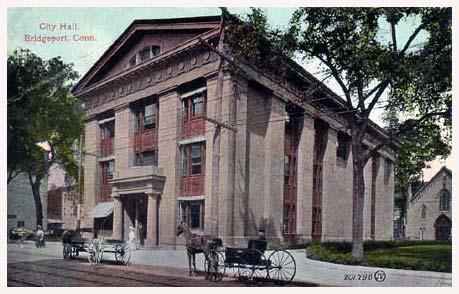

On March 10 of 1860 Abraham Lincoln appeared in Washington Hall, now McLevy Hall (renamed after Bridgeport’s longest-serving mayor Jasper McLevy) with the temerity, fortitude and force of will to appeal to the greater sense of people in the face of incredible odds, ignorance and fear.

Lincoln spoke for two hours, which was described as “an impassioned political speech against slavery.” After his speech, just a minute’s walk to the train, Lincoln returned to New York.

The Daily Standard described a “tall, bony, angular, big jointed figure with a great towering head and very expressive countenance. His eye satisfies you at once that there is brain … intellectual power in the man, and this is the secret of his success.”

About one year after his appearance in Bridgeport, Lincoln received the oath of office as president of the United States. Just weeks after his reelection, a confederate sympathizer pumped a bullet into Lincoln’s brain.

Lincoln had issued an executive order effective Jan 1, 1863:

That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

Enforcement was a challenge relying on the advancement of confederate troops more than two years later in some states.

It is commemorated on the anniversary date of the June 19, 1865, announcement of General Order No. 3 by Union Army general Gordon Granger, proclaiming freedom from slavery in Texas.

After Lincoln’s second inauguration in 1865 he met with Douglass for the final time.

Douglass made the trip to Washington, D.C. to hear the president’s speech, and later attempted to visit him at the White House. White doorkeepers initially barred his entrance, based solely upon his race. However, Douglass negotiated his way into the East Room, where he was happily received by his foe-turned-friend. There, Lincoln said, “I am glad to see you. I saw you in the crowd to-day, listening to my inaugural address … Douglass; there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours. I want to know what you think of it.”16

This meeting, where a formerly enslaved man was greeted by the American president as a “man among men,” resonated with Douglass for the rest of his life.17

Less than two months later, President Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth during a trip to Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Following his death, First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln sent Douglass her husband’s “favorite walking staff” in recognition of the relationship between the two men, and the impact that Douglass’s advice had had on the president.18

Douglass–as Lincoln’s friend, critic, and adviser–perhaps best summarized his thoughts about the president during a speech in 1876, given during the unveiling of the Freedman’s Monument in the nation’s capital:

Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model … He was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men … though the Union was more to him than our freedom or our future, under his wise and beneficent rule we saw ourselves gradually lifted from the depths of slavery to the heights of liberty and manhood.19

Lennie, you can’t print this because it’s “CRT), Critical Race Theory, and it might make little white children feel hurt and guilty.

How we have come full circle or has turned full circle, it is now exactly the same as it used be , for sure no long term memory for the Mayor, no Forth of July for Black and Brown Taxpayers who supported Joe Ganim for Mayor, will they next time?

But again, just Groundhog Day here in Bridgeport, 100 plus marchers from (The Coalition), the mishandling of the deaths of Lauren Smith-Fields and Brenda Lee Rawls–several leading women’s rights, civil rights, and civic organizations marched on city Hall.

I’s Time to Reform the Ganim Administration!

Bridgeport has the Great Street Parade for PT Barnum, you know the guy who talked about a suckers is born every second.