Tiger Ted Lowry was a gem. He was the only boxer to twice go the distance with Rocky Marciano. He was also part of a secret World War II mission “The Fire-Fly Project” that engaged African American smokejumpers in a defense of the Pacific Northwest from Japanese balloon bombs floated across the ocean. Tiger Ted passed away in 2010. This article below first appeared in the June 2005 issue of Connecticut Magazine and is featured in my book Connecticut Characters: Personalities Spicing Up The Nutmeg State. Grab a cup of joe and check it out in honor of Veterans Day.

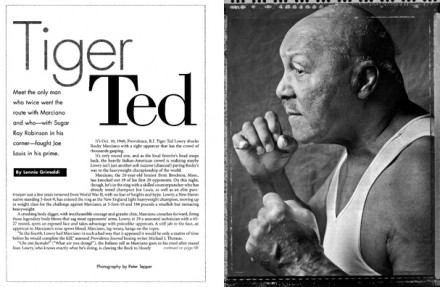

October 10, 1949, Providence, R.I. Tiger Ted Lowry shocks Rocky Marciano with a right uppercut that causes the crowd of thousands to gasp.

It’s only round one, and as the local favorite’s head snaps back the heavily Italian-American crowd is thinking maybe Lowry isn’t just another soft tizzone (charcoal) on Rocky’s way to the heavyweight championship of the world.

Marciano, the 26-year-old bruiser from Brockton, Mass., knocked out 19 of his first 20 opponents. On this night he’s in the ring with a skilled counter puncher, a 65-27 record, who had already tested champion Joe Louis; an elite paratrooper just a few years removed from World War II, with no fear of heights and hype. The New Haven native, standing 5’9-1/2, enters the ring the New England light heavyweight champion who moved up in weight class for the challenge against Marciano, at 5’10-1/2 and 184 pounds, a smaller, if menacing, heavyweight.

A crushing body digger, with inexhaustible courage and granite chin, Marciano crouches forward firing those legendary punches that sag most opponent’s arms. Lowry, at 29 a seasoned technician, spots an exposed face and takes advantage with piston-like uppercuts. A stiff jab to the face, an uppercut to Marciano’s nose spews blood. Marciano, leg weary, hangs on the ropes.

“In the fourth, Lowry had Marciano in such a bad way that it appeared it would be only a matter of time before he would complete the kill,” assessed Providence Journal boxing writer Michael J. Thomas.

“Che stai facendo,” (what are you doing!) the Italians yell as Rocky stumbles to his stool after round four. The Tiger, who knows exactly what he’s doing, is clawing the Rock into bloody pieces. And little does he know history is in the making.

* * *

Ted Lowry was born in New Haven on Oct. 27, 1919. His mother, Grace, a Native Canadian Indian from Nova Scotia, was a nurse, his father, James, worked in the post office, and played organ at the local church. His parents were strict disciplinarians with corporal punishment always looming. “No back talk to my parents,” he says. “They did not believe in sparing the rod. My parents would say, ‘Spare the rod, spoil the child.’”

Nevertheless, the New Haven of his youth was happy and memorable when transportation was horse drawn, street lights were gas lamps, and the icebox featured a block of freeze purchased from the ice man, a pan placed at the bottom shelf to catch the drippings.

“The garbage man, the ice man and the milk man all made their rounds by horse and carriage,” Lowry recalls in his memoirs. “But the horse-drawn wagon driven by the garbage man was the most memorable. In the summertime, his wagon would be teeming with flies. You could smell him coming a mile away.”

The grocery store on Goffe Street was loaded with barrels of molasses, pickles, vinegar and sugar. “There was a pipe running down the barrel with a crank on it which was used to fill the bottle. We used the molasses for pancakes and poured it on biscuits.”

Life then required intestinal fortitude. “My father believed in a spring tonic to clean your system out for the beginning of summer. This tonic was a teaspoon of sugar combined with three drops of turpentine which actually tasted a lot better than caster oil.”

Young Ted played stickball, basketball and football and ran on a track at Beaver Pond Park. Growing up in plentiful Italian American New Haven introduced Lowry to new eating experiences long before the anti-carb craze. “My friend Dominick and I were in the same grade school and used to eat at one another’s house. His mother was a very nice lady but she was huge. When she died the wake was held at the house. But when they went to bury her body, they discovered that she was too big to be carried out the front door. They had to hoist her through the window instead.”

Times were tough for 10-year-old Ted after his father died of pneumonia. He attended Troop Junior High School, hawked the New Haven Journal-Courier each morning for three cents, during Yale University expansion he picked up discarded wood, cut it up, filled bushel baskets and sold it for 10 cents a basket.

The Wonder Bread Company on Broadway baked loaves of bread daily. “We used to go there and get day-old bread.”

His mother kept Ted in school, but clothed him in knickers. “I begged my mother, ‘Please let me wear long pants.’ She would say, ‘You’ll grow up soon enough.’ My mother was in her 40s when I was born and set in her ways.”

Soon they moved to Portland, Maine, to be close to his mother’s family, where Lowry earned his boxing apprenticeship on a lark. A pug advertisement in the paper prompted cajoling from friends. “We dare you to enter.” He was 18 and the only fighting he had done was on the streets of New Haven. “I fought three times that night and won all three times.”

Another newspaper advertisement requested a sparring partner for a professional fighter training for the middleweight championship of New England.

“The challenger needed a sparring partner and someone remembered me. I gave the guy such a working out that my trainer Roy Brooks and ex heavyweight champion Jack Sharkey wanted to take me to Massachusetts to train me and make a pro out of me. I told them they would have to get my mother’s permission. I had been working for the railroad making $18 per week. All the money went to my mother who gave me 50 cents per week as spending money.”

Lowry’s early fights took place as a middleweight in New Bedford, Massachusetts. In 1940 alone he fought 15 times with 11 victories most by knockout. By early 1943 he had boxed more than 70 times when the call came. On May 30, 1943 Lowry was drafted into the army. After basic training, he was shipped to a field artillery unit in Alexander, La. Joe Louis, the heavyweight champion, was traveling to camps for boxing exhibitions to entertain soldiers. “When Louis came to camp to spar all of his sparring partners were banged up, and that meant the soldiers in my camp would not get to see him box.”

Or so they thought. Lowry’s company commander, aware of his boxing background, asked Lowry if he would step into the ring on behalf of the unit.

“Joe Louis was the world champion and I had no business being in the ring with him. I said no, no, no.”

The colonel of the post who heard about Lowry’s reluctance sent a clear message, as Lowry recalls. “I understand you have refused to enter into an engagement with Mr. Louis. There are men on this post who have never had the pleasure of seeing Joe Louis fight. They are going overseas soon and may not come back. Now you can decide on your own, or I can give you a direct order.”

Ted Lowry laced up the gloves with an unexpected corner man for advice, a young Sugar Ray Robinson. The emerging greatest pound per pound fighter on the planet had joined Louis for the traveling exhibition shows. Lowry was already a skilled defensive specialist and Robinson, ever the punch-slipper, provided the following good sense: “Stay in the middle of the ring. Don’t let him get you on the ropes.”

“When Joe entered the ring and they announced his name, everyone cheered and the sound was like a big gun going off. When they announced my name you could have heard a pin drop. I think everyone thought this was a lamb going in for the slaughter.”

Louis knew enough about Lowry that he couldn’t take him too lightly: no embarrassment in front of the troops, especially a national hero, still in his prime, who had avenged Hitler’s gloating with a brutal rematch beating of Max Schmeling in 1938.

Louis applied early pressure. “I think he wanted to knock me down and take it easy. But it was my post and I had to live there after he was gone so I did not want to get knocked down. When round one sounded I wasn’t afraid which was a surprise in itself. Joe was sharp. His punches short and fast, each punch traveling about six inches in length. And he had power. I was only in trouble twice when he backed me into a corner. It was a good thing I was good at ducking.”

Heeding young Robinson’s advice with his own masterful defensive skills, Lowry survived the three round exhibition.

Afterwards, Louis paid Lowry a compliment, saying he had a future in boxing. “You can’t imagine what that did for my ego. I had just been in the ring with the champion of the world, the greatest fighter in the world and he was unable to knock me down. My confidence was inflated.”

Lowry’s ego wasn’t the only thing inflated in the months ahead. The army was searching for a few good men, black men, that is, for a new paratrooper division activated at Camp Mackall, N.C. “I wanted to get out of the outfit I was in and was told if I flunked out of the troopers I would be shipped overseas.”

The boxer, unaccustomed to taking a dive, received a crash course in parachute-landing technique–baby jumps followed by 34-foot high tower jumps with straps attached to his body to absorb the fall, followed by jumps from a 250-foot tower from which the actual chute would open. Next came the real deal. A C-47, rattling and rolling down the runway, loaded with future troopers took to the sky climbing well over 1000 feet.

“The plane was so hot and so noisy you could hardly hear yourself talk. The red light came on in the plane to let the jumpmaster know that we were approaching the drop zone.”

“Stand up. Hook up,” the jumpmaster commanded. Lowry hooked the buckle to the steel cable that ran through the middle of the plane, the strap unfolds and pulls the parachute out of the packs. The green light flashes, Lowry rolls out falling at the rate of 35 feet per second. Suddenly Lowry stops short, the chute opens.

“I checked my chute for any holes and then enjoyed the breathtaking view of the sky and landscape.” He rolled his body, as his feet landed, to cushion the impact. “How excited was I? The only ones who know for sure are the Lord and my laundry man.”

Lowry had four more weeks of advanced training and received his wings in 1944. He became a member of the 555 Parachute Infantry Battalion, the “Triple Nickel,” an elite group of black soldiers stationed in the south for U.S. Army integration.

“We were ‘colored’ soldiers,” Lowry says of those days. “In town if you had to use the toilet there was one for the colored and one for whites. We were good enough to put our lives on the line but somehow not good enough to enjoy some of the things that others enjoyed and took for granted. It was pitiful. Even the drinking fountains at the train station or bus depot were designated “colored” or “white.”

Phenix City, Alabama was particularly hostile. A loaded bus with a black pregnant woman nearly started a riot. A white civilian entering the bus ordered the woman to give up her seat. One of Lowry’s squadron members told the woman to stay put.

“The driver heard the commotion, looked in his rearview mirror, then drove to the center of town, straight to a red-faced policeman. When the back door opened all of the civilian blacks ran out and left us to face the music. We were ordered off the bus and within minutes surrounded by a crowd of white people. They got angry and nasty. It didn’t look good.”

A police captain arrived on the scene.

“Where are you from?”

“Fort Benning (Georgia).”

“No, where is your home?”

“Massachusetts.”

“That figures. You’re not from the south so you don’t know. But you had better get on the next bus going back to camp.”

Discretion being the better part of valor, even for soldiers, Lowry and his crew from the 555 followed the captain’s instructions, “realizing we could have been lynched right then and there.”

Lowry’s paratrooper outfit was transferred from North Carolina to Pendleton Field, Oregon. “Some of us heard we were supposed to make the Normandy jump but at the last minute our orders were changed.”

In 1944, the explosion of a large paper balloon killed five children and an adult picnicking in the Oregon woods. The Japanese had launched thousands of balloons 30 feet in diameter into the jet stream. The balloons were filled with fragmentation and incendiary bombs designed to self-destruct upon descending into the American forest. In response the Army formed “The Fire-Fly Project,” a little-known, fascinating defense of the Pacific Northwest.

“The battalion was assigned the mission of the recovery and destruction of Japanese balloon bombs, with the added mission of the suppression of forest fires started by the aforementioned bombs,” according to U.S. Army archives posted on a web site devoted to the Triple Nickel. “This mission was to be known to all concerned agencies as “The Fire-Fly Project,” and as far as the utilization of airborne army personnel was concerned, was of an experimental nature.”

Hundreds of balloons, according to Lowry’s company commander Lt. Col. Bradley Biggs, reached the northwest United States. Government national security suppressed public dissemination of the Japanese threat during the dry summer.

“We were trained to fight fires,” says Lowry, “but our primary job was to disarm the incendiary balloons. The drop zones were dangerous. We had very little experience disarming bombs.”

In the summer of 1945, armed with specialized U.S. Forestry Service equipment such as fleece-lined flying jackets and pants in place of jumpsuits, basic picks and shovels, the 555 smokejumpers participated in 36 missions with more than 1200 individual jumps on 14 fires.

“Guys suffered crushed chests and broken legs. I was lucky.”

Late in 1945, the war and dry season over, Forestry Service personnel could manage without the 555 smokejumpers. Lowry was shipped back to Fort Bragg and honorably discharged a staff sergeant. (In 1994, 50 years after his service, Lowry was presented an award for distinguished service in support of Wildfire Prevention from the Forestry Service of the United States Department of Agriculture) He returned to New Haven and a boxing career.

* * *

In round five Marciano climbs off his stool a different fighter. Some ringsiders insist Lowry is the different combatant. Marciano slows down the pace with precision and intense concentration. He fires a right to Lowry’s body, a left hook to the head. “That’s when I found out he could punch,” Lowry says.

Marciano pounds on Lowry’s arms. Lowery fights defensively, turning away to avoid the full impact, but posing no counter attack like the early rounds.

“Before Rocky changed his style I was blocking everything he threw.”

Boos and jeers cascade from the crowd of 3,696. Referee Ben Maculan moves in urging Lowry to pick up the action.

“There were some questions as to whether Lowry, who had come close to knocking out Marciano in the second, third and fourth rounds, deliberately bogged down in his attack after the fourth stanza,” wrote Providence Journal reporter Thomas. “Lowry stopped using his uppercut after the fourth (round). He went into a shell and only occasionally landed power shots. He seemed to be carrying Marciano.”

The middle rounds are all Marciano.

The fight fans, although a Marciano crowd, wondered if Tiger had gone in the tank. Boxing enthusiasts of this era had plenty of reason to suspect the fix was in. The fight game was largely unregulated, soiled by shady underworld characters that orchestrated outcomes with promises of bigger paydays for the setups. Do as you’re told or suffer the consequences. After all, a desperate Jake LaMotta, the first to defeat Sugar Ray Robinson, had thrown a fight against Billy Fox in 1948 for a shot at the middleweight crown he eventually won several months before Lowry’s battle with Marciano.

Lowry, who earned $2,500 for the fight, denies he threw the fight for a bigger payday. “I beat Rocky that night and that’s it. He changed his strategy in the fifth round and made a fight of it, but I won two of the last six rounds after winning the first four. It was a hometown decision.”

And the evidence seems more on the side of Lowry that Ted was not in bed with the boxing unscrupulous. In fact even the majority Italian American crowd booed wildly when they heard the unanimous decision announced for Marciano. Overall, the Rock, yet to reach legendary status, had unimpressed the locals. The Providence Journal gave the fight to Lowry.

“Marciano did not win the fight,” wrote Thomas. “This reporter gave it to Lowry, six rounds to four.”

And the big rematch booty, with Marciano a top heavyweight contender, that was supposed to validate Lowry’s play for pay submission did not materialize. The crowd for their second fight a year later (two years before Marciano won the heavyweight title from Joe Wolcott) was twice the size, but Lowry’s take the same $2,500 as the first. The outcome was also the same, a 10-round decision that Lowry concedes to Marciano. But a decision that also stamped Lowry’s place in boxing history: The only man to twice go the distance with Rocky Marciano.

“No one else can say that,” Tiger Ted exclaims proudly, but not boastfully.

Now 85 years old, nearly 56 years after the first fight with Marciano, the Norwalk resident shows none of the punch drunkenness that affects so many in his sport, perhaps a tribute to his defensive deftness. He is trim, speaks lucidly of the past, with no bitterness, about his place in boxing history. “When I fought Rocky the first time I was 29 years old and on my way out, he was 26 and on his way up. If not for Rocky who would know me?”

Certainly the Rock remembered Lowry.

“I think Lowry would have gone the distance if we fought a hundred times,” Marciano, who died in a plane crash in 1969, declared years after their two fights. “I could never get used to his style of fighting.”

Ted Lowry was no paper tiger.