You think this mayoral election cycle is kooky? Try 1981.

Mob hits, car firebombings, the mayor wearing a bulletproof vest, a botched FBI sting attempt against the police chief. These were but a few of the mundane matters intriguing the 1981 mayoral race between incumbent Democrat John Mandanici and Republican Lenny Paoletta who sought a rematch after his hard-driving candidacy in 1979.

Both gave as good as they took.

What a prize for a young reporter to cover. Experiencing bits and pieces in 1977 and 1979, this was my first mayoral campaign start to finish when electoral participation was high and campaign camps lobbed verbal grenades like they were nickels and dimes.

The city’s Democratic registration advantaged only two-to-one, (today it’s almost ten-to-one) with unaffiliated electors the swing vote. Under the right conditions those days Democrats could be choosey too, as was the case in 1981.

From 1933-57 socialist Mayor Jasper McLevy ruled, finally supplanted by Democrat Sam Tedesco who was followed by Democrat Hugh Curran.

Republicans broke through in 1971 when University of Bridgeport administrator Nick Panuzio won the mayoralty.

Mandanici and Paoletta both represented a mighty voting bloc of Italian Americans that had elected one of their own in Tedesco when ethnic voting emerged as pride points.

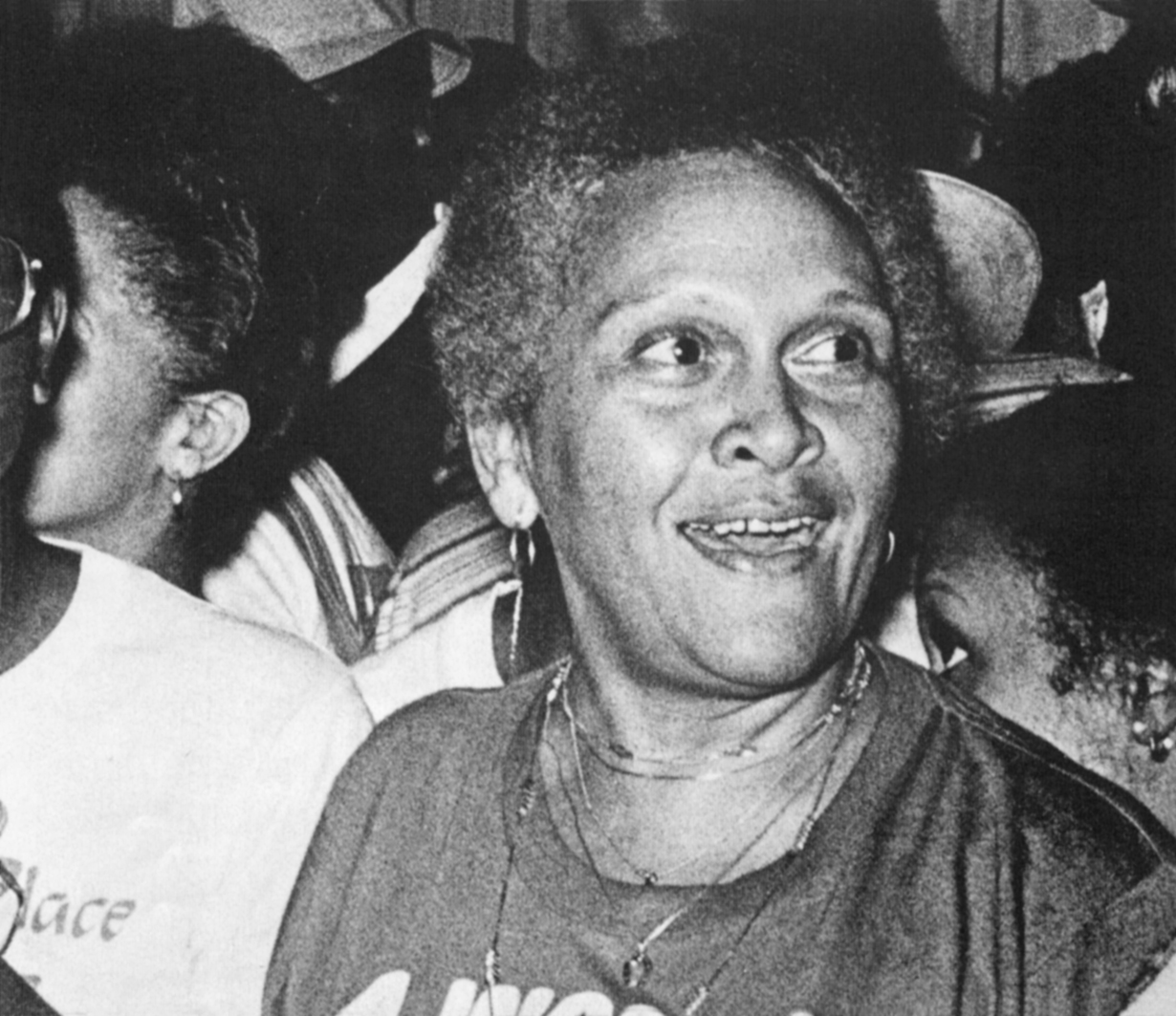

Mandanici had issues with Black voters. One year earlier a kindly funeral home director Margaret Morton turned the establishment on its head defeating party choice Sal DePiano in a Democratic primary on her way to becoming the first Black woman elected to the Connecticut state senate.

In addition, savvy political organizer Charlie Tisdale, who had returned to Bridgeport after serving in the administration of President Jimmy Carter, became a key political linchpin.

Paoletta, a former city tax attorney, capitalized on a series of federal indictments and party infighting that had splintered Mandanici’s administration.

Mandanici himself was told by federal authorities he was a target of a federal grand jury investigation into the city’s Comprehensive Employment Training Act operations, a probe that spread into other aspects of his administration.

The intensity of the campaign was heightened in August when the FBI employed a local car thief, Thomas E. Marra Jr., to lure Bridgeport Police Superintendent Joseph Walsh, a target of a federal grand jury investigation, into a bribe.

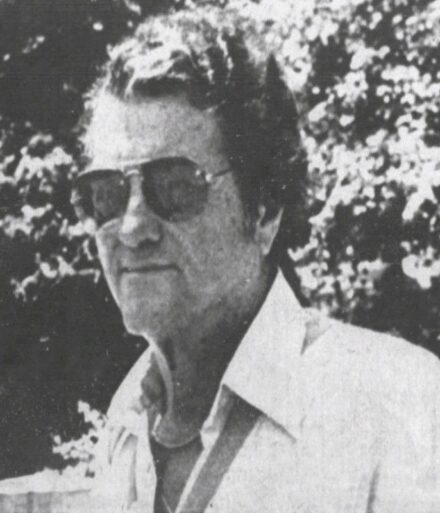

Two months earlier, federal authorities disclosed both Walsh and his long-time associate Inspector Anthony Fabrizi were targets of a grand jury exploring possible violations of the Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organization Act. In Walsh’s 40 years as a cop, he had earned praise as one of the department’s finest officers, a detective who could figure out what phone number a person was dialing just by listening to the dial turn. His reputation was enhanced during the hot summers of the 1960s when Bridgeport avoided the kind of racial violence that plagued other cities during the civil rights movement.

“The Boss,” as almost everyone who knew Walsh called him, or “Jaws” (from his initials, Joseph A. Walsh superintendent) fought with mayors and police boards for control of the department and with minority members of the force who claimed Walsh’s department discriminated against them. Numerous charges of police brutality alleged Walsh’s management style encouraged the beatings. Whatever allegations surfaced, Walsh rose from the clouds of dust as the shrewdest, most powerful and charming politician in Bridgeport.

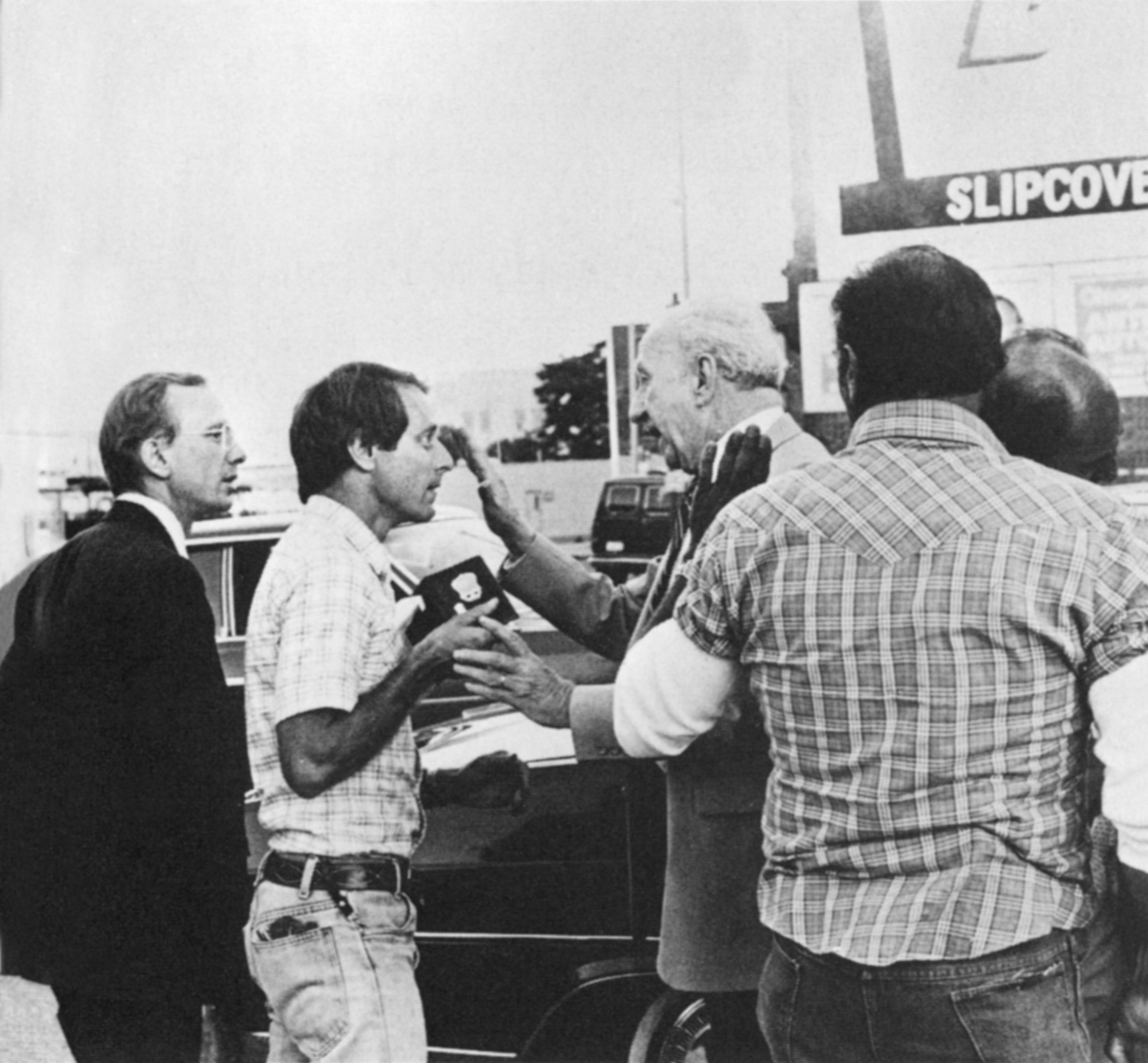

Federal authorities, however, had concluded Walsh not only condoned corruption but also was corrupt himself. They utilized 28-year-old convicted car thief Marra, whose family had known Walsh for decades, to bribe the superintendent to gain back the city’s lucrative towing contract (which Walsh had revoked in May) for his uncle’s garage.

As Marra, following lengthy discussions with Justice Department officials, headed to the Downtown meeting spot with Walsh and wearing a concealed recorder, so too did the superintendent cloaked a recorder, and he crooned the tune “Little Things Mean a Lot” on his way to the meeting. Federal officials hadn’t counted on the fact Walsh was prepared for a setup. While Walsh maintained “it didn’t take a genius to figure out what was happening,” Marra confessed later that the idea of stooging against a man he’d known all his life was too much for him, and he had gotten word to him.

Whatever the stories, it was clear the federal informant did everything strike force prosecutors and FBI agents told him not to do: he brought up the subject of money, got out of his car to talk to Walsh, and then made the bribe offer.

Walsh waited until Marra had handed him the envelope of cash, then arrested him for attempted bribery and called his men who were staked out in the old firehouse on Middle Street, for backup. Mass confusion and a tense standoff between two law enforcement agencies followed as FBI agents rushed to Marra’s assistance and demanded he be released. Walsh refused the agents’ claims while his men dropped Marra’s trousers to his ankles and removed the recording device and then took Marra into custody. (U. S. District Court Judge T.F. Gilroy Daly later dismissed the bribery charge against Marra, ruling that he was acting under the direction of the federal government and lacked criminal intent.)

Photographs taken by Bridgeport Post photographer Frank Decerbo, whom Walsh tipped off to be on the scene, appeared in international newspapers as the botched federal sting led newspaper, television and radio reports. Walsh, for that episode, emerged as the righteous hero, and local government officials squeezed every drop of political opportunity out of the affair.

Mandanici made political hay of Paoletta’s attorney relationship with Marra, claiming Paoletta helped to instigate the federal mission. Paoletta in turn hammered Mandanici for his indictment-filled administration and for further smearing an already seamy city image. He also accused Mandanici of cozy relations with mobsters.

Two months after the sting attempt, Marra’s car was firebombed outside of Paoletta’s campaign headquarters, and a few weeks later, two cars parked in Mandanici’s driveway were firebombed in the middle of the night. If that weren’t enough, Paoletta’s house was burglarized.

In September 1981, two shotgun blasts disconnected Gambino Crime Family capo Frank Piccolo, the most powerful mobster in Connecticut while he stood at a public phone booth on a Saturday afternoon on Main Street.

Just months before, Piccolo had been indicted for allegedly extorting money from the king of the Las Vegas strip, entertainer Wayne Newton. Gus Curcio, who had operated in Piccolo’s shadows in the rival Genovese operation, was arrested in connection with Piccolo’s murder, but was eventually cleared.

Piccolo’s hit, according to court testimony, was ordered by Gambino Boss Paul Castellano who four years later would suffer the same fate as Piccolo outside Sparks Steakhouse in Manhattan, choreographed by John Gotti for control of the family. Gotti’s underboss Sammy “The Bull” Gravano who became the key witness in Gotti’s downfall, revealed one of the reasons Gotti took out Castellano was leveraging a rival family to execute Piccolo.

Meanwhile the Mandanici-Paoletta campaign camps continued the barrage of attacks right into election day.

Most city precincts were exceptionally close with a key outlier: Black precincts came out equally for Republican Paoletta as a backlash to Democrat Mandanici.

When the sparks settled, voters handed Paoletta a 64-vote victory.

Two years later the 1983 mayoral would also become one for the ages.

Damn, thought rent and groceries were up. 🙂

https://www.ctpost.com/news/article/bridgeport-mayor-fundraising-ganim-gomes-daniels-18483323.php?src=rdctpdensecp

How many people voted in that election?

More than 35,00. To compare, close to three times last week’s general election for mayor.

Thanks. I am sure it didn’t cost a million bucks.

Thank God for elections — they’re becoming the largest local employer of Bridgeport residents!…

And; it’s interesting how Bridgeport has become such an undesirable place to do business that even the Mafia decided to close-up shop and head for greener pastures… (: 🙂

Hey Lennie,

Did you ever consider doing an in-depth story on the corruption of the first Ganim administration?