It’s been 33 years since the worst construction accident in Connecticut history left 28 men dead in the collapse of L’Ambiance Plaza, April 23, 1987. I was a 28-year-old communications director for Mayor Tom Bucci. My role was to deal with the media frenzy and announce the dead.

Every year to mark the anniversary, regional building trades are among those paying tribute to the fallen workers on City Hall grounds. This year, due to the health pandemic, the outside gathering will be minimal.

Instead the L’Ambiance 33rd anniversary will be remembered Thursday with a socially distant ceremony at 9:30 a.m. on WICC600 radio. Duane Gates, president of the Fairfield County Building Trades, said the names of the 28 who died–27 men and a teenager who was with his father–will be read on air.

Here’s how I remembered the days in my book Only In Bridgeport.

They were the most gut-wrenching 10 days in the history of the city. Throughout the Downtown and environs, workers and residents perked up at the sound of the rumble. It was sort of like one of those quirky earthquake tremors or a dynamite blast at a construction site.

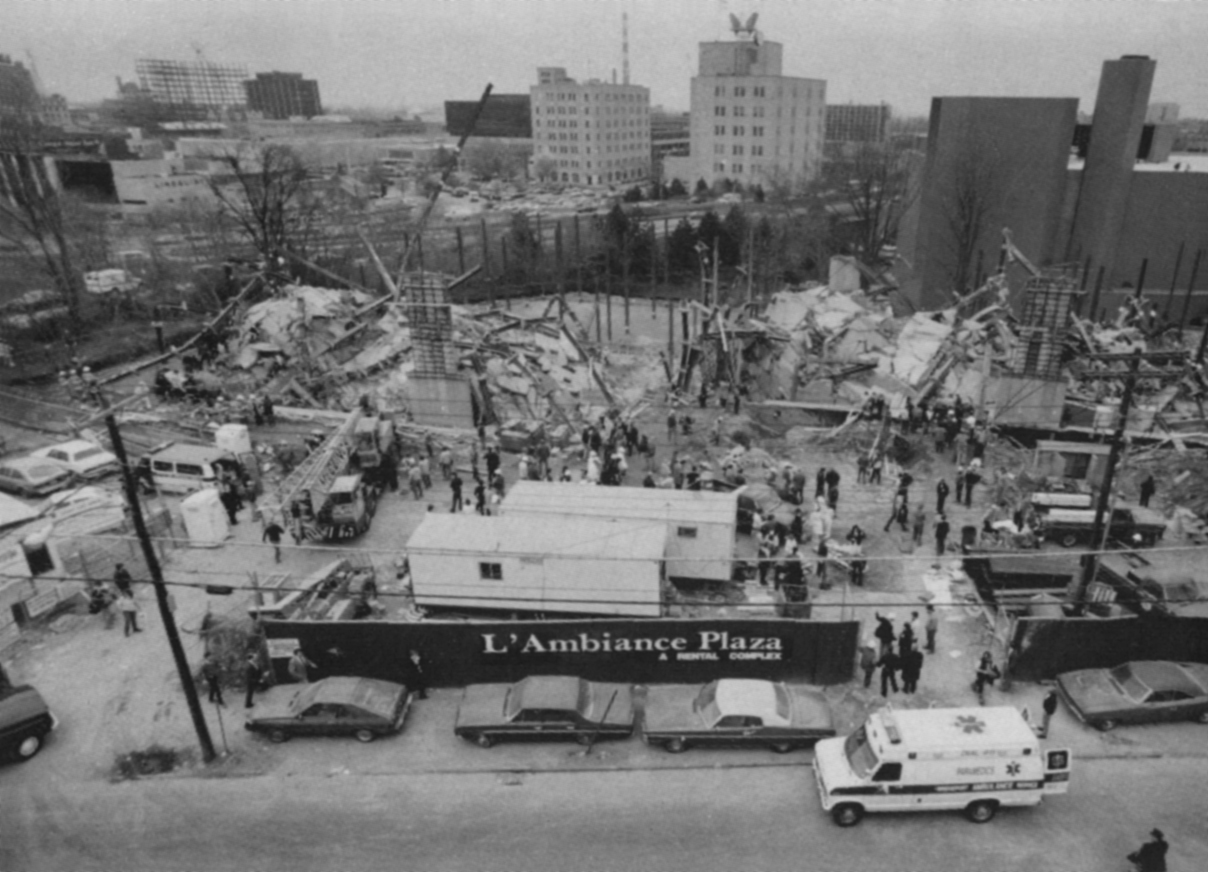

It was April 23, 1987. While lunching at a Stratford restaurant shortly after noon, Mayor Bucci received an urgent call. “Get back to the city. It’s a catastrophe.” Bucci raced back to Bridgeport to discover the horror of a massive building collapse. L’Ambiance Plaza, a half-completed rental housing complex on Washington Avenue overlooking the route 25-8 Connector, came apart, burying workers under tons of twisted steel and shattered concrete, the worst construction accident in the history of Connecticut.

Iron and construction rescue volunteers throughout the country frantically and relentlessly searched the ruins for friends and co-workers buried deep beneath the crush. One by one, crane-removed concrete and steel revealed another body. Days into the rescue mission, microphones were dropped between the cracks in the debris searching for signs of life. It was early spring. Raw days, wet nights, an utterly mad life-saving mission.

“Is anybody down there?”

“Did you hear something?”

“I thought I heard something. Maybe.”

No reply.

Bucci delivered the painful news to the grief-filled families of the victims at a makeshift support facility in the Kolbe Cathedral High School. Monsignor William Scheyd called upon the families to hold hands in prayer.

A massive collection of eager journalists, camera crews and photographers covered every possible nightmarish angle, raided city hall offices for evidence of blame, checked the background of construction companies and dueled with rescue workers safeguarding access to the disaster area and grieving families.

“Keep those idiots with the cameras away from us,” some of the tradesmen would say. A television crew had its power cord cut. An Associated Press photographer had his film ripped away.

Sidebar stories filled newspapers across the country. The outpouring of support by ordinary citizens showed a city with a heart. Psychotherapists helped the families of the victims to cope. Psychics emerged from every direction. “This person’s alive, that one’s not,” they would say.

City Attorney Lawrence Merly took on the state’s powerful insurance companies that were balking at underwriting the city’s disaster costs as the struggle to locate the buried workers continued. Speaking before a crew of national journalists, Merly called the insurance companies “barracudas content to allow the workers to rot in the rubble.” Merly’s rhetoric pried loose an insurance fund of more than $1 million to aid the rescue efforts.

What caused the collapse? Builders had used a construction process called lift slab. Concrete foundations for each floor of the building were poured on the construction site, and then I-beams were jacked up and welded into place. Later, federal investigators made the following determination: the jacking mechanism hoisting the slabs had accidentally slipped.

When it was over, 28 men were dead. A court-approved multi-million-dollar settlement that included the city, state, developers and insurance companies provided families a small pill for a lot of pain.

It was a Thursday and it was Secretary’s Day. The rumble of those floors pancaking was like a roll of thunder.

Never Forget

Larry Merely was a hell of an attorney. It would be an insult to even compare any one in that office today to Larry.

*** A day & time that should never be forgotten aswell, all the construction do’s & don’ts laws that were changed for the better & safety of all involved before, during & after the construction projects are finished.***