The Spice Of Ella Grasso

The Spice Of Ella Grasso

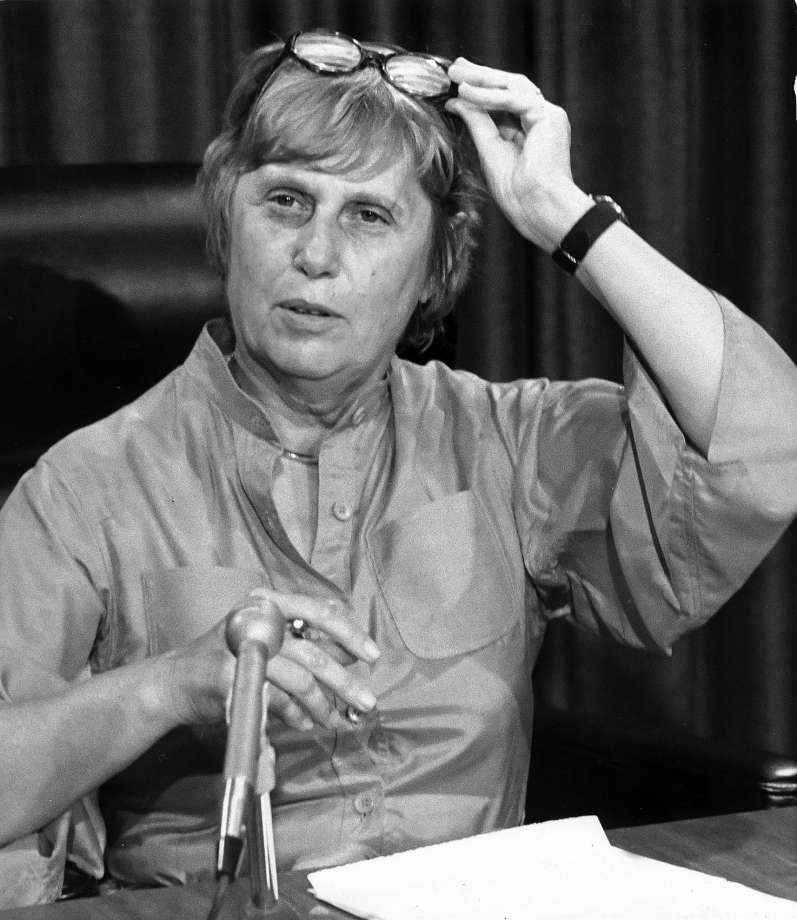

In Connecticut you say “Ella” and that pretty much says it all. In November 1974 Ella Grasso became the first female governor in America elected in her own right without having been married to a former governor. Fifty years ago today, she received the oath of office.

Diagnosed with ovarian cancer in March of 1980, she resigned from office at the end of that year. She died in February of 1981.

In a male-dominated political climate she had no problem keeping up with the boys intellectually and verbally. Actually could they keep up with her?

What follows is an excerpt from my Book Bow Tie Banker published in 2008 that captures a flavor of Ella.

Wesleyan University sits in the central Connecticut hills, a masterpiece of New England colonials and brownstones showcasing a campus that is just a five-minute walk from Middletown’s classic township of banks and restaurants on a wide Main Street.

Established in 1831 and named after John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, Wesleyan, in its early days, was the prestigious academic complement to the city’s community of merchants and farmers barging goods from Middletown down the Connecticut River and into Long Island Sound.

Middletown was a bustling enclave in early Connecticut, the state’s highest populated and most prosperous municipality. Its thriving port and citizenry were heavily involved in maritime and merchant activities. Then, stormy American-British trade relations, and the resulting War of 1812, curtailed port momentum. And when officials of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad decided, 25 years later, that routing the Hartford-to-New Haven through Middletown was indirect and expensive, the city was shut off from the railroad’s main line.

Middletown’s reliance on water transportation left a small base of manufacturing jobs that attracted thousands of Sicilian immigrants as mass migration from southern Europe flooded Connecticut cities around 1900. The Sicilians worked at Wesleyan as well. Masons, custodians, landscapers and cafeteria workers filled the labor pool at the university whose niche as a center for language, literature and science — rather than theological training institution — was a magnet for scholars and the social elite.

Technically not Ivy League, Wesleyan’s academic reputation was closely comparable to Yale, just 15 miles to the south. Along with Amherst and Williams, its liberal arts neighbors to the north in Massachusetts, Wesleyan was known as Potted Ivy — a protected group of prestigious, and highly selective, Eastern liberal arts colleges. Wesleyan was noted for producing an eclectic group of writers, runners and rockers — such as Robert Ludlum (Class of 1951), Bill Rodgers (Class of 1970) and John Perry Barlow, (Class of 1969) who penned songs for The Grateful Dead. The university was so exclusive that the school featured maid service in the dorms. Maids would actually change sheets and tidy rooms for the young, privileged gentlemen, before the school eliminated that benefit around 1971.

With all its educational success, however, Wesleyan was a stranger to its host city. The prevailing student attitude was to ignore the Downtown, and the college administration’s indifference to Middletown’s political and neighborhood infrastructure created a large town-gown divide. A few businesses tried to lure students Downtown. Bob’s Surplus, the clothing store, held an annual sales campaign: “Come to Bob’s and get a free laundry bag.” So it was a laundry bag at Bob’s, followed by a grilled cheese at O’Rourke’s, a Main Street diner famous for its metal interior. But mostly, the university and its students, pretty much ignored the adjacent city.

By 1970 the university was playing social catch-up with the times. Female students finally were admitted as freshmen that year, six decades after school administrators had eschewed that egalitarian approach. Back in 1910, male alumni complained that equality between men and women curtailed academic standing, so the school stopped admitting females. It took administrators 60 years to realize that women could also be smart.

The slow speed of gender parity was not exclusive to Wesleyan. Many of America’s elite institutions were gender-challenged until the 1970s. But something else was blowing in the wind. And it was much more than the reefer sweetness accompanying a free Grateful Dead concert on Foss Hill, overlooking the campus athletic field, on May 3, 1970. Issues like Vietnam, race relations, political activism, co-education and a disdain for the establishment had coughed up a revolution infecting college campuses across America.

Wesleyan was poised for transition, and change was all around. Colin Campbell, the university president, made a great effort to reach out to new student constituencies. Recruitment of females, black Americans and Latinos was an active part of the transition. Involvement with social agencies, such as the YMCA and the United Way, and affiliations with business and political establishments, were on the rise.

Italians, by sheer force of numbers, controlled Middletown politics, while the WASPs ran the business community.

In 1979 Michael Cubeta, a young, idealistic Democrat, was elected mayor of Middletown. At the time, an option was being negotiated for a prime 287-acre tract of land in the heart of Middletown’s industrial park area adjacent to the Town of Cromwell. The property had previously been proposed as a site for a thoroughbred horseracing track.

Connecticut Governor Ella Grasso was not a fan of expanded legalized gaming in a state that had already introduced jai alai and the state lottery system to enhance state revenues. Cubeta was called to a meeting at the governor’s office to discuss the latest proposal. He was introduced to a team of Aetna executives, including Robert Clarke, Robert Gai and Richard Coughlin. Grasso explained that Aetna had optioned this tract in Middletown to build an 800,000 square foot facility, intending to relocate its employee benefits division from Hartford.

The governor explained that in order for the plan to proceed, Aetna wanted state assistance, including a sizeable appropriation from the General Assembly to construct a bridge linking Route 372 to a widened Industrial Park Road leading into the site. The company was also seeking tax abatements from the City of Middletown pursuant to a state statute permitting a municipality to abate up to 100 percent of real property taxes for a period of up to seven years for economic development projects.

Grasso, the first U.S. woman governor ever elected in her own right, was at the height of her popularity. Only a year earlier, the Blizzard of ’78 had buried the state in a record-breaking snow. Ella, a Democrat, had not forgotten what a snowstorm had done to the approval ratings of her Republican predecessor — who was skiing in Vermont while a storm paralyzed the state. Come election time, voters iced Thomas Meskill.

Ella took charge at the State Armory, ordering all non-essential traffic to stay home while state and local crews plowed roadways. She was present, visible, direct and reassuring. By the end of it, she was Mother Ella, the snow queen. Voters rewarded her with an overwhelming re-election victory.

Grasso was so far ahead of her time that she transcended gender politics. With that short crop of brown, turning white, hair and that hunter’s stare, she looked like a school principal, and cussed like a prison matron. This daughter of Italian immigrants had a commanding presence. Grasso asked Cubeta to remain behind after the meeting. She told Cubeta she would work with the Legislature, and the State Bond Commission, to secure the capital for the bridge and road work, and that Cubeta needed to negotiate the tax abatement agreement with Aetna and get approval from the Middletown City Council. Cubeta recalled the final exchange with the governor:

“This is the largest economic development project in the state’s history,” Grasso advised Cubeta, as she walked him to the door. “Don’t screw it up!”

“I won’t.”

“This is quite a bit better than a dog track. Wouldn’t you agree, mayor?”

“A horse track, governor,” Cubeta corrected.

“What the hell’s the difference?”